Doom: House of Hope

Doom: House of Hope

Epic Theater + Cultural Cut Up + Transcendent Beauty

By Anna Ehrsam

Anna Ehrsam is an Art Historian, Writer and Artist based in NYC

Anne Imhof’s Doom: House of Hope at the Park Avenue Armory is a spectacle of rupture and dissonance, a work that embodies the collapse of meaning while exposing the ideological structures that uphold it. Imhof constructs a Gesamtkunstwerk but through a Brechtian lens, where disruption, estrangement, and contradiction force the audience into a space of critical awareness. The performance resists cohesion, negates narrative closure, and operates in the interstitial zones of différance, where meaning is perpetually deferred (Derrida, Margins of Philosophy). Doom is both critique and participation, a work that foregrounds the impossibility of stable signification within a hyper-mediated cultural landscape.

Imhof’s structural choices align closely with Brechtian Verfremdungseffekt, or the alienation effect. Rather than immersing spectators in a fictional world, Doom disrupts expectations at every turn. The audience is not allowed to settle into passive consumption; instead, they must navigate the 55,000-square-foot Drill Hall, encountering fragmented scenes, overlapping actions, and unresolved gestures. This is the theater of interruption, montage, and contradiction The detachment fostered by this technique forces the viewer to see the constructed nature of performance itself, thereby encouraging critical reflection on both the spectacle and the systems it critiques.

Imhof's use of multiple, simultaneous performances distributed across the space rejects traditional narrative coherence. There is no singular plot to follow, no catharsis to be reached. Instead, Doom unfolds in disjointed episodes—what Brecht might term "historicization"—where performers oscillate between detachment and intensity, presenting gestures that comment on social conditions rather than merely representing them. The presence of Romeo and Juliet in reverse order functions as a meta-theatrical gesture, laying bare the construction of tragic inevitability and inviting audiences to question the fatalistic narratives they consume in culture and politics.

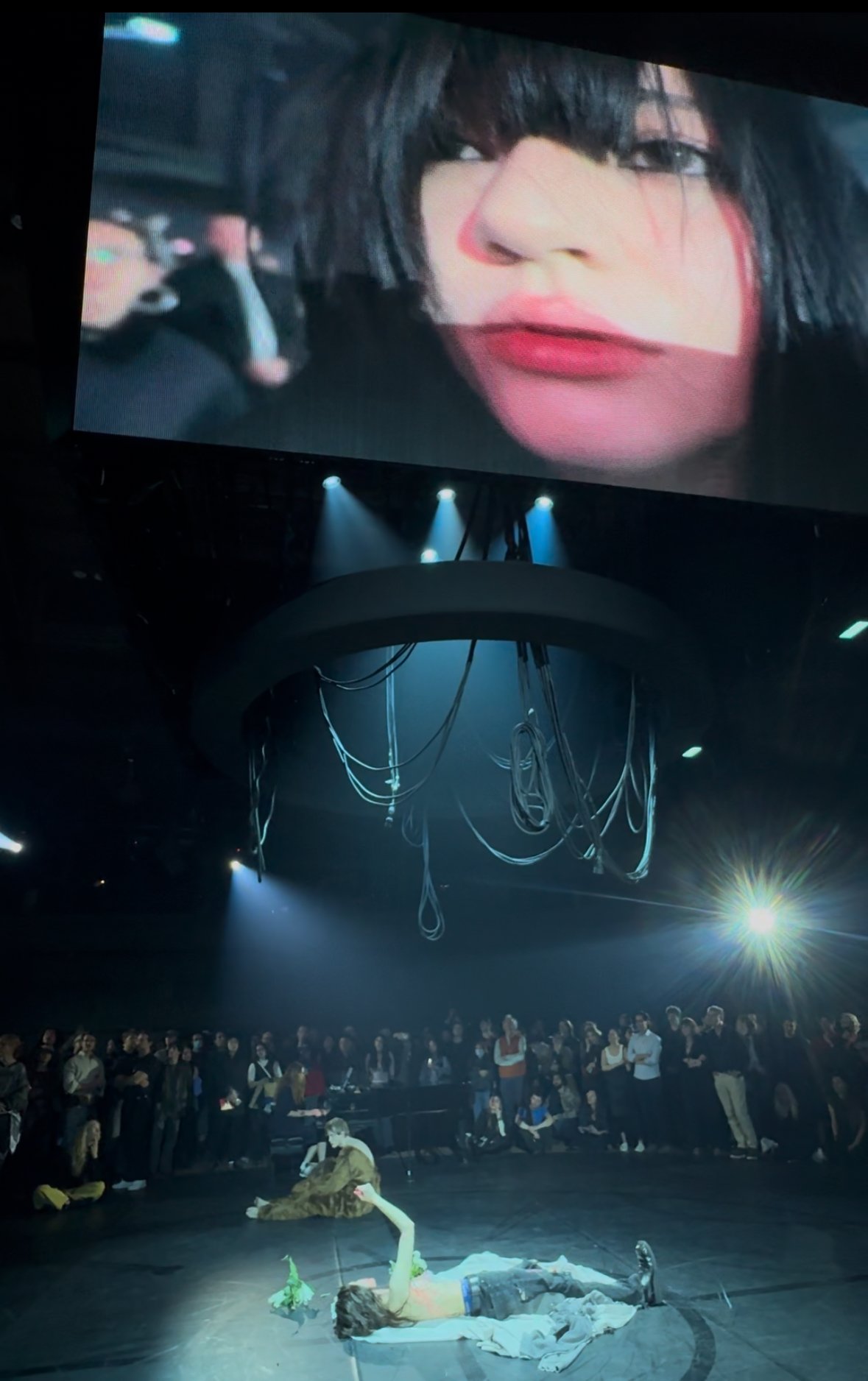

Doom operates as a site of différance, where meaning is suspended, fractured, and multiplied. The staging of luxury goods—Cadillac Escalades doubling as stages, tattoo parlors set in their trunks—functions as a détournement in the Situationist sense, an appropriation and subversion of capitalist spectacle (Debord, The Society of the Spectacle). However, this is not merely a critique of commodity culture; rather, Doom enacts the Derridean process of deconstruction, revealing how every symbol within the performance both signifies and undermines its own significance. The Jumbotron that towers over the event, broadcasting live-streamed images of the performance, collapses distinctions between presence and mediation, the live and the recorded, the original and the simulacrum.

Imhof’s performers, staring blankly into the distance, muttering in monotone, or embodying bursts of affective excess, perform the very instability of identity and authorship. Their presence within the work is not stable; they are both subjects and objects, both signifiers and signified. Their movement through the space enacts a form of textual play, one that resists resolution and instead fosters what Derrida might describe as the endless deferral of meaning (Of Grammatology). The audience, by capturing and transmitting the work through social media, becomes complicit in this process—neither fully external to the work nor its authoritative interpreter.

Doom functions as a hijacking of familiar cultural symbols, turning them against themselves to expose their ideological underpinnings. The juxtaposition of American high school aesthetics—basketball jerseys, cheerleaders, line-dancing—with high art references such as Balanchine ballet, Shakespeare and Bach destabilizes aesthetic hierarchies, reframing cultural codes through processes of inversion and collision. Yet, as Debord warns, détournement is always threatened by recuperation—the risk that its subversions will be absorbed back into the very spectacle it seeks to dismantle.

In Doom, the process of recuperation is foregrounded rather than hidden. The audience, many of whom arrive as self-conscious participants in an aestheticized event, become part of the work’s commentary. Their compulsive documentation—the Instagram stories, the fragmented clips uploaded in real-time—reinforce Debord’s thesis that “the spectacle is not a collection of images, but a social relation among people, mediated by images” (The Society of the Spectacle). Imhof does not seek to resolve this contradiction but rather amplifies it, allowing Doom to function as both an act of resistance and an acknowledgment of complicity.

While Doom deconstructs, estranges, and subverts, it does not surrender entirely to negation. The emergence of structured ballet in the final hour introduces the possibility of form, of discipline, of aesthetic transcendence. Devon Teuscher’s solo beneath the Jumbotron—a moment of poised, deliberate movement within an otherwise chaotic field—suggests that within the deferral of meaning, within the critique of spectacle, there still remains the possibility of art as an act of presence.

Amidst the chaos, dissonance, and alienation, there exists an undeniable and overwhelming sense of sublime beauty. Imhof’s world is not merely one of critique and fragmentation; it is also one of breathtaking, almost transcendental moments of aesthetic clarity. The stark contrast between the raw physicality of movement—dancers poised atop Escalades, bodies entwined in languid repose, sudden bursts of violent, ecstatic energy and the delicate precision of a ballet creates a space where beauty feels both fleeting and eternal. The lighting, at times stark and clinical, at others suffused with an ethereal glow, heightens this effect, illuminating bodies like moving sculptures against the cavernous expanse of the Armory. Music, too, shapes these moments—the melancholic strains of Ville Haimala’s “fog 1-3(after Bach),’’, the haunting echo of The Doors’ The End—lending an emotional depth that transcends mere spectacle. It is beauty not in the traditional sense, but in the Romantic, almost Kantian understanding of the sublime: a beauty that unsettles, that overwhelms, that makes one acutely aware of both their own smallness and their infinite potential. In Doom, beauty is not passive; it is charged, demanding, transformative. It is an aesthetic experience that does not soothe but awakens.

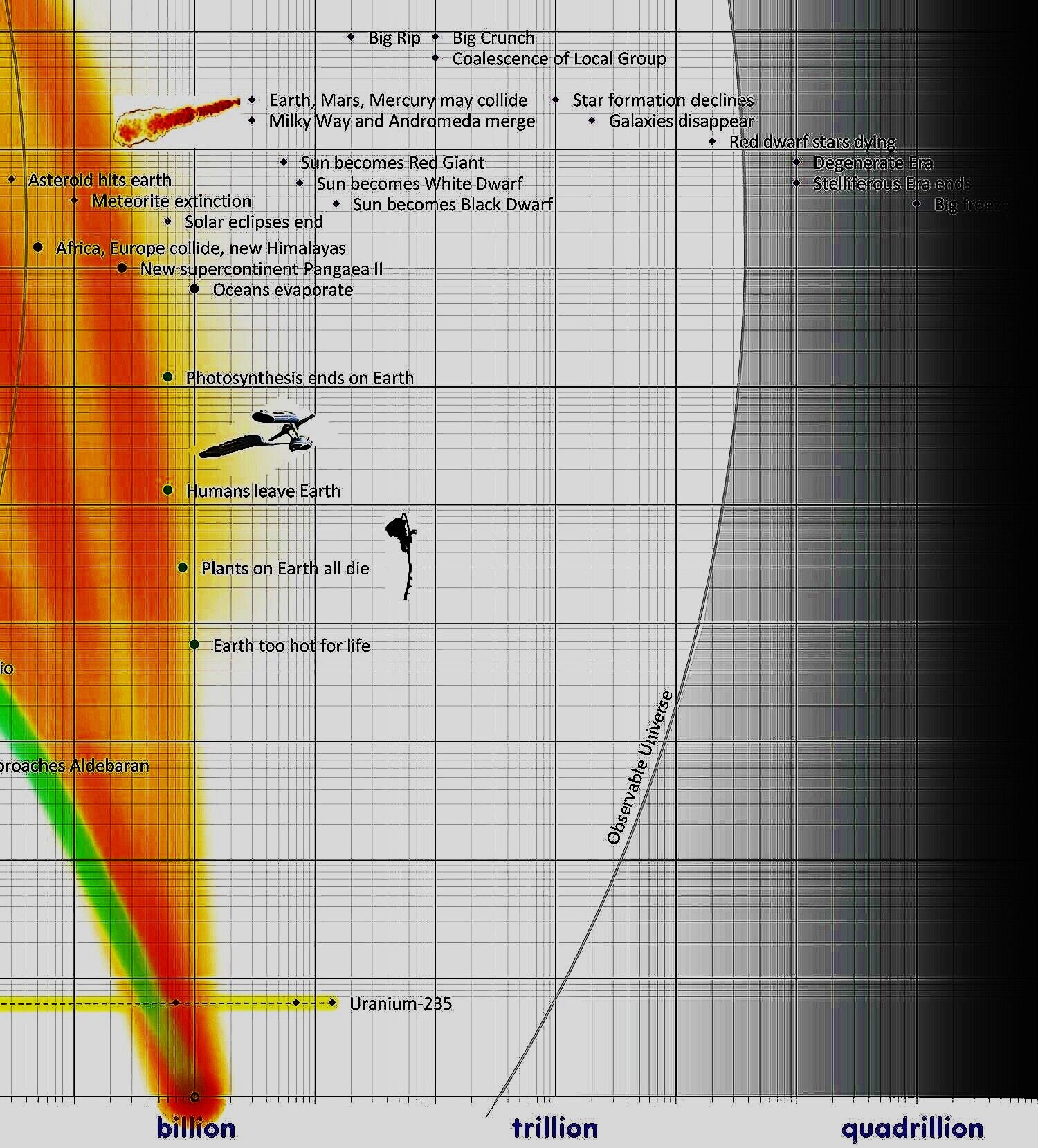

By reversing the narrative of Romeo and Juliet, Doom does not merely undo tragedy; it gestures toward the hope of rewriting. If Derrida’s différance teaches us that meaning is never final, that every text is haunted by what it excludes, then Imhof’s work suggests that art, too, can remain open—unresolved, uncontained, and in perpetual motion. This is not the empty hope of escapism, but the radical hope of potentiality.

Imhof’s Doom: House of Hope is not an artwork that provides easy answers. Instead, it forces us to inhabit the tensions of our time—the dislocations of digital mediation, the contradictions of capitalist spectacle, the instability of identity and authorship. Doom does not simply critique the structures it exists within—it performs them, reveals them, and holds them open for interrogation.

As the countdown clock reaches zero, as the audience disperses, what remains is not closure but a lingering question. If the role of art is not to resolve, but to make visible the fractures in our systems of meaning, then perhaps Doom offers us not just a critique of the present, but an invitation into a future still waiting to be imagined.