I Was A Hired Gun

by Ben Goldman

I Was A Hired Gun

An untold story from the front lines of the battle for environmental justice

to envision a world of skillful interrelatedness.

© Ben Goldman 2021

Dr. Wild Ben Goldman talks about his work with the environmental justice movement as it relates to his work in the field of health and wellness with artist Inventor Anna Ehrsam.

FIRST SHOT

Mingling in the lobby of an upscale Washington-DC Omni Hotel where the first meeting of the EPA’s National Environmental Justice Advisory Committee was about to take place, some African American leaders of this emergent social movement asked me, suspiciously, “what are you doing here”?

I said, “I’m a hired gun,” and they recoiled.

Several may have been there as observers and were surprised to hear I was one of the select few appointed by the Clinton Administration to the charter membership of the Committee. None of them knew this twenty-something Jewish kid from New York City was the key author behind the landmark 1987 study that propelled the movement to national prominence, forcing the creation of a Presidential Executive Order and the formation of this unprecedented federal advisory committee in 1994.

My statistical study for the United Church of Christ Commission for Racial Justice (CRJ) proved for the first time that toxic pollution reflected nationwide patterns of discriminatory behavior, from which the term “environmental racism” was coined. Up until then, the environmental movement was largely just another space for white privilege, focused more on protecting birds and bunnies than black and brown people from the disproportionate impacts of industrial wastes. Communities of color and lower incomes were fighting polluters locally across the country, but a national movement had yet to emerge.

It was my privilege to be hired by the Commission, then led by the Rev. Dr. Benjamin F. Chavis, Jr., who seven years prior was freed from his lengthy imprisonment as the leader of the “Wilmington Ten,” a group of young Black men wrongly convicted of committing arson during their civil rights activism after the assassination of Martin Luther King, Jr., for whom Chavis had once worked as an assistant. Our study’s prominence helped catapult him to lead the NAACP, a position he then held for just 16 months, after which he was abruptly dismissed for his secret settlement of sexual harassment allegations filed by his own executive assistant.

I was the youngest of a trio of Jewish radicals (aged 25, 55 and 75) who co-founded a firm called Public Data Access, Inc. (PDA), at the forefront of the digital revolution, dedicated to providing greater access to government information. We were “hackers” before that was a term. I had just published my first book, the first national study of the commercial hazardous waste industry in America. We were also the first people ever to provide public access to the U.S. Census broken down by zip code areas, and so we were in a unique position to do this kind of geographic-based socioeconomic and environmental research.

Some maps from The Truth About Where You Live: An Atlas for Action on Toxins and Mortality (Times Books, 1991).

The Commission paid us a mere $10,000 to do the study, which we spent entirely on various expenses associated with obtaining and processing the data. So, I volunteered my entire summer designing the analysis and running highly sophisticated multivariate tests. I also submitted it as a research paper for the advanced statistics course that allowed me to skip the foreign language requirement of my doctoral program at NYU. I got an A+. My first ever, I believe.

I worked hand-in-hand with Chavis’s lieutenant Charles Lee, an Asian American who, ironically, was a chain-smoking Harvard dropout that went on to direct the EPA’s Office of Environmental Justice. After several failed attempts that summer, we were ecstatic when I was finally able to prove unequivocally the dismal reality that people of color and lower incomes were suffering disproportionately from adverse environmental impacts across the country.

A typical response at the time came from Assistant EPA Administrator J. Winston Porter, who told the Washington Post, "there's no sociology to it," referring to the siting process, "it's strictly technical." (Yeah, right!)

We used the National Council of Church’s definition: “Racism is racial prejudice plus power. Racism is the intentional or unintentional use of power to isolate, separate and exploit others.”

Believe it or not, in that study, I think I was the first person ever to define what a person of color is using the United States Census (in current terms, BIPOC = total population - non-hispanic white; prior to that, all studies of which I’m aware kept each race and ethnicity separate).

But soon everything turned on its head for me.

CANCELLED

When I received my first copy of the final report, I noticed my name was listed in the acknowledgments rather than on the title page along with Chavis and Lee. The name of my company was there, but not in the same font size as the Commission’s, which their attorneys had specified in the contract I signed. The National Writers’ Union agreed to represent me if I chose to sue the Commission for violating my author rights, but I chose to let it be, in order not to hurt the cause.

Mind you, I wasn’t just some newbie consultant at the time. I’d already directed a multi-year project at a nonprofit called the Council on Economic Priorities that included spending months visiting toxic waste sites across the country, meeting with community leaders to tell their stories, assisting with technical expertise, and publishing a major exposé of the toxic shell game that was happening in America. I was also a leader in my own community in the fight against the Brooklyn Navy Yard Incinerator as a founder of the Lower East Side Coalition for a Healthy Environment, a fight that helped launch the political careers of many Latinx leaders who still hold positions of power in New York City to this day.

As president of PDA, I was hired by many dozens of local and national environmental organizations, activist groups, governments (including tribal), and even private corporations to conduct studies about myriad environmental harms across the United States and internationally, including many groundbreaking topics such the existence of “cancer alley” along the Mississippi, proving that the U.S. military was the largest generator of toxic wastes in the world, helping stop the expansion of nuclear power in Canada, uncovering excess deaths from low-level radiation, and, in general, pioneering the use of what’s now known as “big data” in the public interest.

My company was one of the finalists in the bid to run the federal Toxics Release Inventory, which was the first congressionally mandated online public information system (they chose the National Library of Medicine instead–we would have done it better, recommending a map-based system that wasn’t created till years later). The Reagan Administration even sued my firm for releasing data on who buys Congress, which eventually led to a Supreme Court victory, a precedent overturned by Citizens United. CRJ even agreed to be the fiscal sponsor for an effort of ours called the Radiation and Public Health Project, which continues to operate as an independent nonprofit organization to this day. I spoke and testified at national venues in Washington, DC and across North America on these and other related issues. My work was praised by Al Gore and widely featured by ABC, CNN, NPR, USA Today, The New York Times, The Washington Post, and other media outlets.

In 1991, I cut my Yucatan honeymoon short to deliver a keynote speech at the First National People of Color Environmental Leadership Summit. But when I returned from Mexico, there was no message indicating the exact time and place of my address. When I called the summit war room for details, I could hear Charles Lee shouting to the person who answered, “just get him off the phone.”

I attended anyway since my travel plans were already set. Nobody there even knew my name. It took twenty years for others to update my work (though my first update for the Commission and the NAACP was published in 1994). They cite me multiple times, but never bothered to ask for my participation or comment in any way.

Instead, I found myself being hired mostly by white-led organizations that were interested in my “street cred” as an environmental justice activist as well as my analytical and leadership skills to help to establish the notion of “green jobs”, including directing the organization that coordinated the participation of U.S. non-governmental organizations in the Rio Earth Summit, which first brought international attention to the concept of sustainable development, and eventually being appointed to the President’s Council on Sustainable Development and authoring Sustainable America for the federal government.

Yet the further I rose in the world of mainstream environmentalism, the more disillusioned I became by the work. It seemed ever more removed from addressing the greatest harms that were disproportionately affecting the people most at risk.

I ultimately left the field.

THE DISTINCT INSTINCT

You might call my experience in the environmental justice movement an example of “reverse racism” (a racist term itself), a case where “prejudice plus power” was turned opposite its typical direction. Or maybe that combined with ageism, because I was so young at the time I did that seminal work, or antisemitism, and maybe personality factors were involved as well.

My perspective, however, is that everyone is racist, or more precisely, has an “inner racist,” similar to other internal psychological structures such as our super egos. It’s part of what I call the “distinct instinct,” our basic ability to discriminate this from that and to identify with one, not the other. You might call it “duality” or even “object relations” (how our earliest conscious distinction of ourselves as a subject–especially from the object we call “mommy”–becomes our personality). These are instinctual and unavoidable perceptions and reactions. What is avoidable, however, are behaviors that act on those discriminations in ways that harm or subjugate others and ourselves; in other words, that misuse our “power”, personal, organizational, and societal.

Identity and power are so multilayered and multivariate—or “intersectional”, a term coined by Kimberlé Crenshaw, a leading proponent of critical race theory (CRT), two years after the Toxic Wastes and Race study was published (indeed, she cites our report, which may be the very first national quantitative study of intersectionality, in her history of CRT; although, I doubt she’s aware of my role in designing it).

Identity is not as simple as a dichotomy between true self and ego. Just as our familiar self is a construct of personal history, so are race, gender, and most other identifiers social constructs of history at large, which, in turn, influence our own personal histories and the sense of our familiar self. It’s the institutionalization of these constructs that cause the most harm over time.

The Mask Series (2021, acrylic on paper, 17” x 22”).

Similarly, it’s not as black and white as distinguishing true power from false or a single story of privilege and fragility, no matter how dominant the narrative and systems of white supremacy may be. And be forewarned, the distinct instinct is the basis for all modern technology, replicated in the binary code at the core of all artificial intelligence that will soon control so much of our world. Implicit bias is just the ugly underbelly of distinctions we find useful, a juxtaposition that itself is just another duality.

Clown Mask (2021, augmented reality).

Or try my "snapcode" using Snapchat to transform yourself or any face you want into an unintentionally creepy clown mask:

An early insight of the environmental justice movement was that the leadership of environmental organizations had to change complexion to encourage more diverse participation in environmentalism and to yield societal change. The first Black man now leads the EPA, but there have been other people of color in that position before, and, of course, that’s just one of the many positions of leadership in the multi-billion-dollar constellation of national and international environmental organizations (let alone the leadership of trillions of dollars worth of organizational polluters). Race is just one of many dimensions of diversity, and diversity is just one element needed for wise leadership, robust organizations, and sustainable societies.

The first time I met Chavis, for example, he made one of my partners and me wait over an hour outside his office door without ever offering an explanation or apology. That’s never happened to me before or since, but certainly felt like a raw demonstration of power, no matter what was the Reverend Doctor’s original intent or what that behavior foreshadowed. (Never happened, that is, in the context of a scheduled business meeting that’s important to both parties; of course, waiting like that happens all the time with doctor appointments, government services, and even sought after dates, where the imbalance of power is palpable.)

In so many ways, the changes we need seem far too slow in the face of far too-urgent dangers.

THE PERSONAL IS POLITICAL

It’s personal for me. My own work has of course involved understanding my own history as it relates to these and other issues, but also my present circumstances and identities, which include being the father of a young person who identifies as a white man even though he was born a Black girl. This is all the more wild for me, because, in a way, he's even more Jewish than me, having become a B Mitzvah, which I never did, due to intergenerational pressures of assimilation. So, we’re both members of a 3,000-year-old self-identified race that somehow, he and most everyone else within the last generation or two has conflated with the very same dominant race that tried to exterminate us.

I’ve also experienced the responsibility of wielding positions of power and leadership, along with their many difficulties, racially charged and otherwise, personal and political. Silly me: I left public policy for the arts, which may be even more consumed by identity politics than the field of politics itself.

In short, I’ve been largely erased and cancelled from the history of a pivotal social justice movement that was spearheaded in part by a young Jewish man who was hired by an Asian American working for an arm of a mostly white Christian church led by a charismatic Black minister who misused his power and ultimately converted to Islam.

How intersectional is that? It’s probably not the story of environmental justice you’ll hear anywhere else. When The New York Times Magazine featured a history of environmental justice in 2020, for example, you might be led to believe it’s a Black-only movement, and that thousands of activists such as myself were not involved from the start or that poor whites are not also disproportionately impacted along with people of color (ironically, I grew up in the largely Black neighborhood of West Philly where the article begins). White washing and Black washing both contribute to the historiographies of our times, most recently in the form of “memory laws,” and most likely of the whitewash variety, reflecting the preferred narratives of those in power. Racism is way more fluid and prevalent than most people want to acknowledge. It manifests through acts of omission as well as commission. It can become institutionalized even in well-meaning liberal organizations, unless intentional countermeasures are taken, and even despite them, given the overarching historical context.

So unlike when I began this tale as a hired gun, using technical expertise as a weapon for change, I’m no longer interested in being a mercenary even for a good cause.

This work requires a different level of skillfulness entirely.

The Mask Totem (2021, work in progress, mixed media)

SKILLFUL CHANGE

After decades of work focused first on societal change then on organizational change as a leader of various for-profit and nonprofit enterprises (with lots of creative and artistic work along the way), I turned my attention to personal change, the kind of self-development and spiritual work needed to live life fully within a world so entangled by human strife and conflict. That’s the focus of Nature Breakthroughs, my current venture and the title of my latest book (which explores these issues in much greater depth). It’s informed by many traditions, one of which is a mystery school, in which it’s “my privilege” to participate, called the Diamond Approach. I’ve learned so much from them, and originally proposed this essay as a topic for their exploratory group on “inclusive cultural inquiries,” which focuses on “increasing cultural wakefulness.”

They rejected it, citing two reasons: that I am not “well known” to them, and I’m not a person who is “least represented” nor someone who “[doesn’t] have a safe and open place to express their experience.”

Well, it seems to me that what I’ve written (as well as my participation in the school for the past eight of their 43 years of existence) makes clear who I am and what are some of my struggles and talents, and that their exclusion of my perspective within the context of such extensive personal work makes equally clear there are very few opportunities for me or anyone to explore these issues in ways that question prevailing orthodoxies on the right and left (thank you to Battery Journal for being an unexpectedly rare exception).

The day following that rejection letter, another set of teachers from the school in the specific cohort where I’ve been learning for nearly a decade also independently rejected pleas from others in the group to discuss similar issues relating to cultural diversity, saying “they have not unfolded as a core thread of the teaching.” Ugh. The notion that spiritual development can begin with examining our personal psychology and end with a nondual awakening, bypassing all of the sociological occlusions in between seems patently absurd and foolhardy to me.

I’m continuing to participate in the school, because it remains the most comprehensive and well-developed integration of psychological and spiritual work I’ve encountered. I also continue to recommend it to anyone interested in doing deep work to develop their own self-awareness. But even this exceedingly broadminded school reflects the limits of the society in which we live, with an individualistic approach to enlightenment and a business model that yields a constituency of mostly older, wealthy, liberal white folks who can afford the work. It’s “my privilege” to participate in the school both in that respect as well as because of the deep healing that the work has offered me.

The skillfulness required to change oneself, the organizations where we work, and the society in which we live requires better ways of being as well as acting. Inquiry, the wise and fundamental practice of the Diamond Approach, is always a good starting point, but, from my perspective, is insufficient without action. So I am taking this opportunity to express these undoubtedly controversial thoughts, and though it’s not my intent to offend, I’m expecting as much disapproval as affirmation.

Is this just an essay about a personal grudge, a self portrait of the many masks I’ve worn over time, or does it have greater significance? I am definitely amazed that these events from early in my adult life still trouble me to this day, and continue to inquire into that. I, for one, however, believe it’s more than just personal. Overcoming our racist tendencies, blind spots, institutions, and politics requires more than diversity and inclusion programs, though that’s a necessary and important starting point. Neither systemic racist harms nor white rage and fragility will disappear until all sides are heard in a respectful and empathetic manner, and beyond that, the systems must be changed.

Most importantly, the environmental harms generated by our entire species will not be reversed without overcoming the bitter partisanship created by the lack of such empathetic communication. And make no mistake, these harms are threatening not only our own survival but also that of our “more than human” co-inhabitants of planet earth. What environmental justice teaches us is that these harms are never distributed equally; but rather, always have disproportionate adverse effects. We need to be very concerned about the proverbial canary in the coal mine, both because such canaries deserve a life without disproportionate harm, and because they signal danger for us all. Unless we hear the cries of sentinel beings and feel them as our own, necessary action will inevitably be too late.

NOT A METAPHOR

The canary is a great metaphor.

Everyone wants to keep the canary alive and well: that signals it's OK to work in the mine. This touches on why "intention" isn't a necessary ingredient in detecting racism; implicit biases are unintentional by nature yet are even more ubiquitous and thus cause even greater harm. The canary is also probably paid a living wage for its services in the form of ample bird seed to survive. But compensation doesn't justify the situation, since the canary isn't there of its own free will, rather, is probably caged, all in subjugation to human economic pursuits.

Canary revival cage with oxygen cylinder as handle (Wikimedia).

Now, since canaries aren't endangered, such economic uses don't threaten the survival of their species, so proponents could argue it's a valid tradeoff. There are many kinds of canaries, so you'd have to take care which one you select for such an argument to fly. Endangered populations of other "indicator species" do indeed warn of impending doom on a grander scale, just as bird calls have been cogent warnings audible for miles for anyone in the wild who understands their meaning since time immemorial. Such knowledge was once ubiquitous among humans but is now largely lost as is so much of our connection to the ways of the natural world… also at our own peril.

But all this misses so many underlying structural issues, such as what the heck are we doing in the coal mine along with that canary in the first place? Sure it creates jobs and electricity that generate myriad benefits for humankind, but there are substitute sources that don't cause climate change, smog, black lung disease, mountaintop removal, deforestation, river pollution, community-obliterating landslides and collapses, and all the other disproportionately destructive local and global adverse health and environmental impacts of this now-largely obsolete power source.

And then there's also the history of the captivity of these birds since the 17th Century by European imperialists and aristocrats, as well as their domestication, forced breeding and commodification.

A single dead canary is not only an urgent alarm to evacuate an entire mine—one unlucky casualty to save many lives; it can also be seen as a fatal indictment of an entire system if we look closely enough.

Look even closer and you can see it's not a metaphor at all. Humans have really done all this not only to the canary, but to other humans as well: Blacks turned into chattel, whites sent down the mines.

THE BIG PICTURE

For visual learners, here’s a diagram that makes the implications of environmental justice clear. It shows three dimensions of equity analysis (social, geographic, and intergenerational). Influential parties located somewhere in this space are likely to make decisions that benefit them and whoever they represent more than those located elsewhere in the space, unless there are procedures that give voice to beings in other locations within these dimensions, so that they can also influence the impact of such decisions.

Three Dimensions of Equity Analysis (not including cross-species).

This is how NIMBYism works (not in my backyard), how the “first” world causes harm to those in the “third” world, how our generation causes lasting harm to future generations, how the wealthy damage the poor, men oppress women, whites enslave or discount the welfare of people of color, how colonizers exterminate native inhabitants… and all that’s just what humans have done and continue to do to each other. Add a fourth dimension (not easy to do in a two-dimensional diagram) for cross-species impacts, and it becomes just as clear that we need legal mechanisms (such as the Endangered Species Act) to give voice to non-human lives, so they can be protected as well.

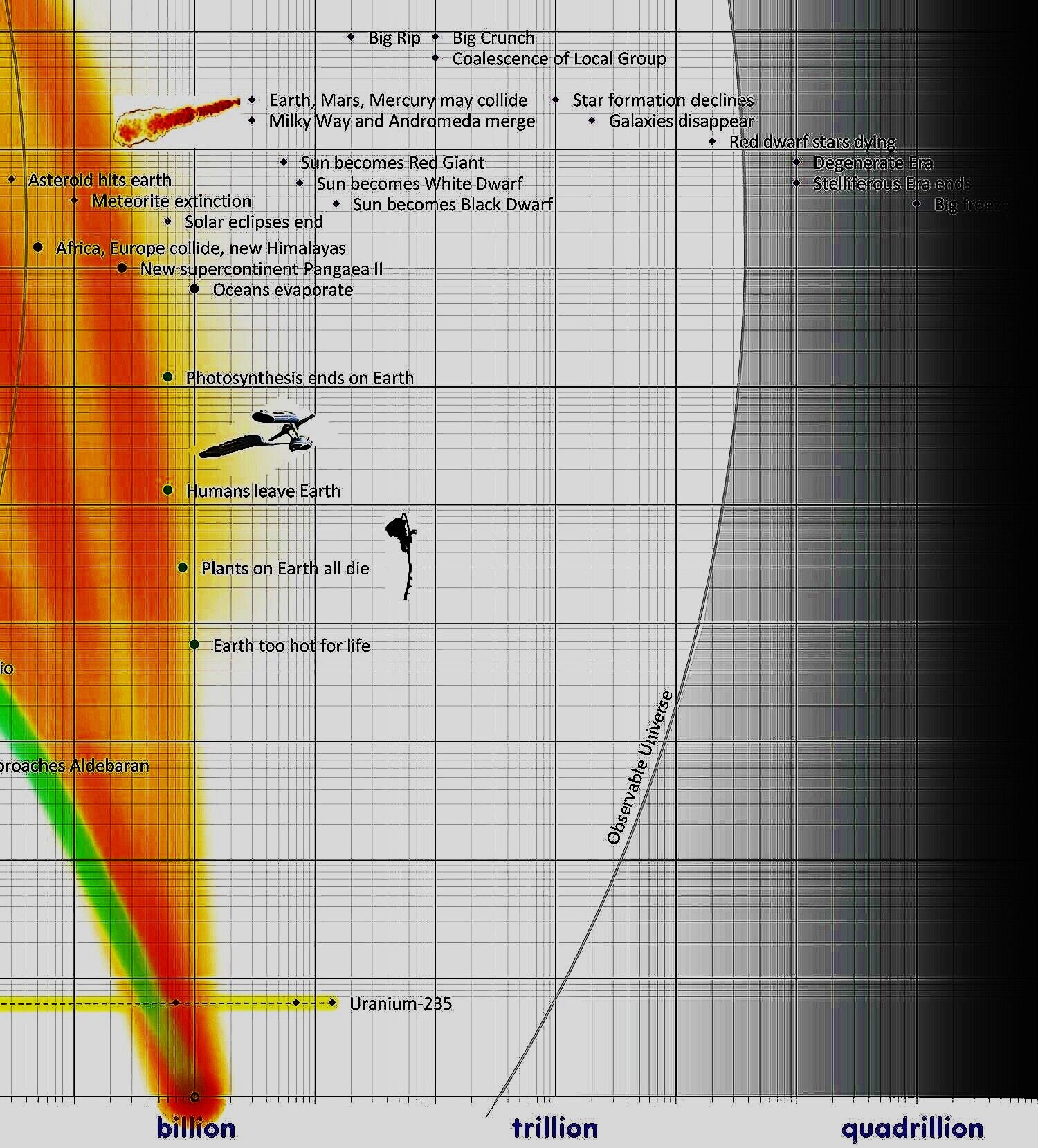

An even bigger picture of the situation can be seen in my “Visible Universe,” which uses data analytics and visualization in similar Cartesian coordinates (juiced with some modern mathematical tricks like E=mc^2 to make time a universal currency) to map the entire history and future of the universe in a single image, from the Big Bang 10^−10 (13.7 billion) years ago to the postulated Big Freeze in another 10^14 (a hundred trillion) years, and with everything in between—including all we’ve ever experienced here on earth (empire, war, migration, slavery, invention, dinosaurs, etc.). It shows how everything is related and quantifiable using inverse logarithmic scales to look backward and forward in time, dilating the present moment or wherever you wish to focus your attention. The Visible Universe is like a Google Maps for time. It not only scales from microbes to galaxies but can also show with surprising precision the curve of the 108 billion Homo sapiens who existed since the beginning of time to the current population of nearly 8 billion. How harrowingly finite that is: one out of fourteen humans who ever existed are alive today.

Here’s a version of it created as a kind of self portrait (the last one I’ll offer for this essay... unless you find Waldo in the subsequent video). In addition to my own projected lifespan (and yours), it shows how certain technologies we’ve created in the recent past are already destined to last till the end of life on earth (along with their attendant hazards), when it will be necessary for the last of us to leave the planet, and so much more....

A History of the Universe as a Logarithmic Self Portrait

(2012, archival print, 17” x 44”).

This is an example of how our technologies could be improved to show how we’re all connected: to each other, to our pasts and our futures, on this planet and elsewhere. It’s far more than a pedagogical tool. In addition to enabling every student to see where they fit in the universe, the technology could improve every digital experience from comparison shopping to selecting flights, sports betting to family trees, email, social media—every single human-computer interaction. It’s a data-driven user interface for accessing everything we know and seeing how it’s all related from the beginning to the end of time. The gap in the center indicates how the present becomes infinite mathematically due to the inverse logarithms, a spiritual touch that I particularly like.

I prepared a patent filing for all of this, but ran out of steam after I tried to apply my insights to Facebook. It was the perfect culmination of all my work in project management, innovation, data, technology, and the arts. I decided to test-run the idea with an app called “Foam for Facebook'' to demonstrate how the Visible Universe could be used to enhance the experience of interacting with people, posts, places and events on the largest social media platform on earth. I knew exactly what I was doing. All the planning, preparations and mockups were done. While hiring Belarussian programmers to build a minimum viable product, I found myself responding to their requests for more and more granular instructions staring at my computer monitor for days on end, totally unable to complete the simplest spec sheet. Despite my enthusiasm for the grand vision, its enormous business potential, and all my work leading up to that moment, there I was, stuck again. So I continue to move on….

Foam for Facebook Pitch (2016).

LAST SHOT

I offer the following inquiries for anyone who would like to continue this urgent yet lifelong journey of discovery with me:

How do you experience diversity and racism in your work and life in terms of the people and content you encounter? What do you appreciate and what’s missing? How does it make you feel? What needs to be done to diversify participation in your work? What’s your relationship to intersectional prejudice and power? Have you heard or can you hear the racist inside of you? What would you say to it? How must our systems of social media, public policy, organizational culture, education and economics be changed so we can all hear the canary and act together for our own good and the good of our fellow earthlings?

Special thanks to Michael Rees and his team and guest presenters at the SculptureX workshop at William Paterson University where my Mask Totem and Snapchat Clown Mask were created, including Roman David Brown, Collin Hassler, Christopher Manzione, David D'Ostilio, Michelle Thursz, and Olaf Unsoeld.

Dr. “Wild” Ben Goldman is founder and CEO of Nature Breakthroughs, which helps people find their true nature in nature, getting unstuck, on purpose. He works with executives, entrepreneurs, and creatives, and cohosts Transgender Living with Change (TLC): a free weekly support group for parents and family of transgender and gender-expansive people. Dr. Goldman’s career has included leadership positions in the public, private, and nonprofit sectors, spanning topics from technology to environmental activism, social justice, and the arts, including appointments to the federal government, a supreme court victory, and groundbreaking research that created a new social movement. As founder and president of United Visual Arts LLC, he invented the patented defEYE® frame sold by the Museum of Modern Art. The New York Times called City Without Walls, which he directed, "one of the most socially engaged and dynamic art spaces." He is a widely published author, and museums and galleries throughout the world have exhibited his art. His doctorate in public administration is from NYU and his latest book is Nature Breakthroughs: 5 Steps to Transform Yourself and the World.