Joel Tauber's Vision of A Better World

Joel Tauber’S social Praxis

Activist. Artist. Filmmaker. Joel Tauber sparks discourse and facilitates change via direct actions and interventions, video installations, films, photographs, public art, podcasts, and written stories.

“Tauber can be as poignantly eccentric as German performance jester John Bock, and as profound as Joseph Beuys.” – Emma Gray, ArtReview Magazine

I had the pleasure of speaking with Joel Tauber about his new Film and exhibition entitled Border-Ball. You are invited to watch BORDER-BALL from April 29 - May 1 at https://www.artcenter.edu/connect/events/artnight-pasadena.html

Bio

Here's the NBC 7 story,

And here's the Spectrum News story

Project website:

ArtCenter College of Design exhibition page for Border-Ball

https://artcenter.edu/borderball

Border-Ball movie screening on the ArtCenter website from April 29 - May 1:

https://www.artcenter.edu/connect/events/artnight-pasadena.html

Movie trailer:

https://vimeo.com/joeltauber/borderballmovietrailer

Resources page:

https://borderball.net/participate/

Or more specifically:

Learn more about how we’re treating immigrants:

https://borderball.net/resources/

Share your thoughts and stories about immigration and borders

https://borderballstories.tumblr.com

Do what you can to help

https://www.freedomforimmigrants.org/join-us

A Conversation with Joel Tauber About Social Practice & His Project Border-Ball

Anna - Joel Tauber is an activist, artist, and filmmaker. He teaches at Wake Forest University as an associate professor. Tauber sparks discourse and facilitates change via direct actions, interventions, video installations, films, photographs, public art, podcasts and written stories. His projects include: Border-Ball: A 40-Day Pilgrimage Along The U.S. – Mexico Border, BELT: A 2-Man Memoir, UNDERWATER: An Operatic Disco, The Sharing Project, Pumping, Sick-Amour, Searching for The Impossible: The Flying Project, and Seven Attempts To Make A Ritual. https://joeltauber.com

Thank you Joel, for being here.

Joel - So good to see you, Anna. It's wonderful to connect with you again. We were students at Yale University together. You were a graduate student, and I was a lowly undergrad discovering art. And I just wanted to say to you, but also to everyone, that you were one of the people who taught me a lot when we were together at Yale, and I won't forget it. You know, I learned a lot from you and from the other grad students when I was there—I’m thinking specifically of Robert Wysocki and Sergio Vega—in addition to learning from our professors. I've been thinking a lot about lineage and the ever growing community of learning that we share, especially when I teach and when I find myself learning from my interactions with my students. I also learned a ton from our teachers too, of course. The conceptual artist and critic Ronald Jones was brilliant, so sad he just passed. I also learned a lot from Rachel Berwick. You know, it was a beautiful time in a beautiful place. There was just so much energy happening there, so inspiring to see all the amazing projects that were being created there. We were in that big gymnasium together, you know; and I don't know if that's still there, but that's where all the magic happened. There were just amazing things happening all the time. And it was inspiring, you know, seeing what's possible. People creating things with these big ideas and trying to contribute culturally and make a difference. So it's great to talk with you again now.

A- It's lovely to see you again. It's really a pleasure. I remember when we were at Yale University, one of our first conversations was surrounding the art making process and praxis, really the daily practice of it. And I recall you saying that your work was like a prayer or a meditation. Will you speak to that?

J- Yes. First of all, you have an amazing memory. My sense is that the metaphysical was also something that was of interest to you, as it was and still is for me. One of the things that really stuck in my mind about what Ronald Jones taught me was: I remember him talking about how art can facilitate change. How it can generate discourse and literally create change. And I think that was part of the energy that was happening at Yale, all these people really excited and committed. And I think one of the things that got me captivated and excited about making art was how it fostered a kind of openness. And to me that was in a way like meditation. And I think being open is hugely important because it also fosters empathy. It helps us understand our environment. It helps us recognize our interconnections with each other. I studied Jewish philosophy and religion for 12 years, in Hebrew and ancient Aramaic, before I came to Yale. I was going to be a doctor before I stumbled into a sculpture class with all of you. And then that was that. I was thinking a lot about ethics, and I was thinking about our connections and responsibility to each other. So when I started making art, it was coming out of that context for me. I wanted to make work about ethics and responsibility. It really resonated with me—this idea of trying to put something out there that can be helpful and that can maybe lead to addressing some of our problems. And so this idea of openness, I think, was helpful for that. And then also there is the idea of prayer. You mentioned Seven Attempts To Make A Ritual, my project where I was trying to figure out ways to construct a spiritual or ethical practice outside of organized religion.

We have a lot of problems. There's so many problems, ethical and environmental crises that we face. So putting something out there and hoping for it to make a difference, there's a prayer there in a way. And so I think about it in my practice in general, as a way to try and to contribute, to try to address problems, to raise conversations. And there's a leap of faith there. So no matter how many huge problems we're facing, I think there's always hope, and I try to have my work embody that hope, to foster a kind of openness and hope and then possibly spur action.

A - Absolutely. That's really a beautiful answer. I'm thinking about your current project on view at the Williamson Gallery at ArtCenter in LA.

J - Yeah. The Williamson Gallery at ArtCenter College of Design, where I went to graduate school and where Ron Jones ended up becoming provost. The world is small.

A - I just wanted to give our audience a little primer about the exhibition and specifically this conceptual art project, which is entitled Border-Ball: A 40-day pilgrimage along the US - Mexico Border. I have a press release, I'll just read a few lines to help contextualize the project. Border-Ball. Conceived at the height of the immigration debate during the Trump presidency, conceptual artist Joel Tauber embarked on a 40-day pilgrimage along the U.S. - Mexico border. Deeply unsettled by the amplifying division and separation in the U.S., he wanted to turn the tables on the conversation by fostering connections and community. The result of his poetic and activist gesture is Border-Ball, a site-specific installation exploring how the dynamics of trust and open dialogue can bridge the growing rifts of fractured societies. Presented on the heels of Tauber’s award-winning film of the same title, Border-Ball is currently on view at ArtCenter’s Williamson Gallery: from March 10th through June 4th. There is also going to be a watch party.

J - There's a few different layers to this project. I mean, the first one you were talking about: my pilgrimage down to the border. A social practice project where I walked every day for 40 days along the U.S. - Mexico border, beginning at the Otay Mesa Port Of Entry near San Diego. I lived sort of near there, in LA, for a long time. That was the part of the border that spoke to me, or that I felt most connected to. I walked every day from the Port Of Entry, along the Border Wall, and then up to the Otay Mesa Detention Center—and back. And so that performance, that action, that social practice project was the first manifestation of this work. And it was also about trying to build community. I was playing catch with people at the border. I was in this baseball uniform, a custom-made baseball uniform of blue, white, and red—because it was a patriotic act.

My grandparents, my paternal grandparents, survived the Holocaust. My grandfather's brother died in a slave labor camp. And the march in Charlottesville, where people were yelling about killing Jews and Black people. All the racist rhetoric. All the locking up of refugees—many of whom don't have any criminal records whatsoever. There is physical abuse happening in our detention centers, sexual abuse, forced labor.

I believe in what our teacher taught us: how art can make a difference, how it can facilitate change and create conversation. This was my attempt to try to do something about some of our problems, to go to the border and to foreground this idea, this belief, that we at least profess to believe in, this idea of diversity, this idea of openness. Openness, like a big green field where there's room for everyone, or like how people can go to a park and interact or play with anyone - even strangers. Doesn't matter where you're from. That idea of openness, bringing it to the border where we’ve become way more closed.

I was inviting people to walk with me. To talk with me. And also to play catch with me. It was like sharing a drink. It was creating conversation. And it was a way to form connections in a place where we were heightening differences: with our barriers and with our Wall, and then at the Detention Center there–with three layers of barbed wire. So I wanted to challenge that through those juxtapositions. And I tried to create community. I met so many people. I talked to people from all different walks of life: border patrol, guards, detention center guards, people who live in the United States with papers, people who don't, people who are walking every day across the border and back. People shared many hopeful stories and also very many sad stories.

So, walking every day for 40 days and linking the Port Of Entry where we are more open, where people are coming in and out, to the Detention Center and the Wall, where we are extremely closed. And we're not supposed to think about our detention centers. We have them all over our country. And I wanted to bear witness.

One of the people who walked with me was Christina Valentine. We went to grad school together at ArtCenter, and she's now the director and curator of ArtCenter DTLA. We had planned to do an exhibition of the installation version of the project in 2020, and then the pandemic hit. So, I finished editing the movie version of the project a bit earlier than I had initially planned, and premiered it on the ArtCenter website in October 2020, a bit before the U.S. elections. The movie is 20-minutes long and it’s been on the film festival circuit for about a year and a half now. It’s called Border-Ball as well. And it’s screening next on the ArtCenter website (again) from April 29th to May 1st. Here's the direct link for people to be able to see the movie.

Now there’s also an installation version of Border-Ball. It’s on view at the Williamson Gallery at ArtCenter now through June 4th. The installation is very sculptural. I've got sculpture roots. I think about filmmaking sculpturally too. And so the installation has nine videos - nine innings - which are only viewable in person, in the installation. It’s the largest version of the project, there's more video material than in the 20-minute movie, and people experience it in an active way. So, the space–it's a large space, 4,600 square feet, I believe. People walk in, and there is a baseball field, and the baseball field is composed of the videos and the video equipment. There's a pitcher's mound with a monitor–an actual mound of dirt. That video has the story of my pilgrimage, while the other eight videos feature the stories of some of the people that I met.The installation highlights eight different people that I met, and they're presented as eight videos in the baseball field. There's four of them on iPads–as the bases. There's three of them projected really large as the outfielders, and then there's a catcher or umpire on a large flat screen. They are telling different stories, first person accounts of some of the things that are happening to them.The installation—as well as the movie—is a way to foreground and amplify their stories.

A - You talk about your mission and your desire to bear witness and bring attention to the social and political issues that are affecting the quality of life for people and the planet.

J - Right.

A - What spurred you to action? You have a real sense of social responsibility and a mission to help people. You said that you have a direct family connection to historical events that were traumatic with lasting generational effects which have perpetuated pain, and an awareness of how a people's history and context can shape their lives and the lives of subsequent generations. Your family lived through and experienced the Holocaust and for generations after felt the effects of the psychic trauma, cultural trauma and global trauma. We could say those events still have resonance that you feel today. Did that spur you to action? I feel it too. You have this political and ethical awareness of what's going on with immigrants at the Mexico - U.S. border, you have an empathy for the families and people coming here who are trying to seek a better way of life for their children and families. It is important to be aware of what our government is doing in our name. The U.S. government implements inhumane, unethical practices and policies pertaining to how immigrants are caught and imprisoned, families separated, children taken from mothers and irreparably lost in the US system. These policies are unspeakably evil, and this is a mass kind of trauma. The way most network news sources have handled this crisis at the U.S. - Mexico border weaponizes the plight of the refugees who are captured and stripped of their personhood. The way the news spins the plight of the people creates a kind of reaction formation against them and weaponizes the crisis. I can't even watch the news anymore unless it's Democracy Now, free speech with fair reporting and intellectual rigor. How can art help? Through the lens of art, and an intellectual, philosophical, poetic practice you're helping me to readdress this incredibly pressing issue of what is happening to the families who are being detained and whose human rights are being violated. Last I heard, thousands of children that were separated from their families were lost in the system, in foster care, when they have families who desperately want them back. The agencies involved couldn't find the families again. What is happening with the detention centers now and the families? What is the policy now at the border? And in terms of detaining people that are coming here trying to find employment or trying to seek asylum from really unlivable conditions let's say at the border or border towns, no resources, there's environmental racism, and injustice going on there of the most extreme magnitude. What spurred you to take action? I feel that supporting you in your project and to help enlighten others is a way I can help in some small way. How can other people take action? Are there resources that you can share with people that will help them? Because I think people often feel that by watching the news they're being informed and being informed is enough. And so then they're part of some kind of spectator relationship with the trauma that is ensuing and continues to persist. Watching the news and thinking about it, is that really enough? Is that doing much of anything? And how can people go from that kind of conceptual space of considering what's going on? An action starts with the thought certainly, but then how to make the next step. How can Border-Ball help them? How can you help them? How can we help them with resources and activism?

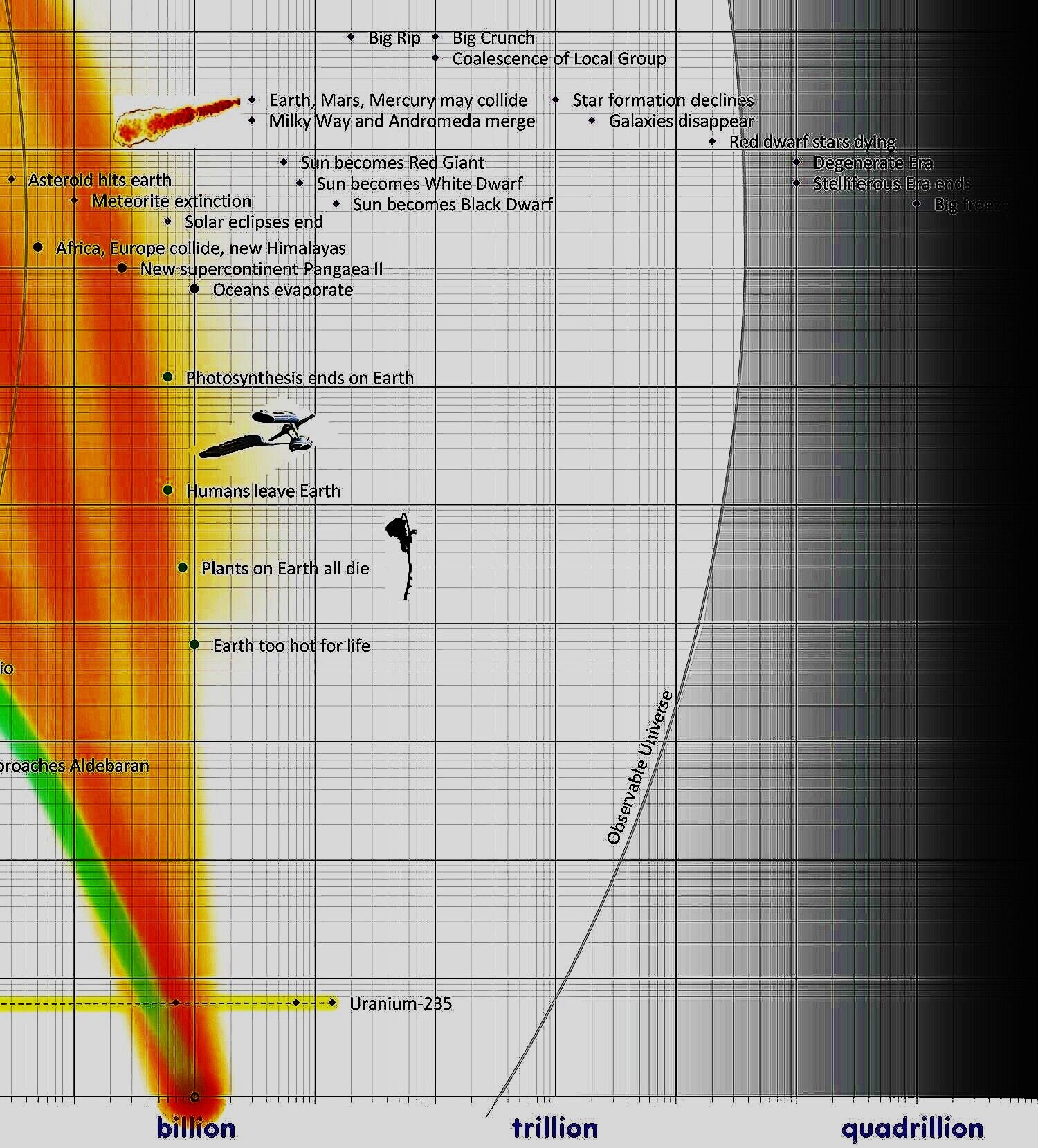

J - Yes. I loved everything you said, you know. Just to reiterate some of the things you said, because I believe in them so strongly. How when there is suffering anywhere, we're all feeling it in some way because we're all connected. How knowledge is important, but it's really only important if it helps us act and move forward and try to improve things. How when people are suffering, it impacts everyone. How trauma can impact people for generations. And how the refugee crisis is also connected to the environmental crisis. The environmental crisis is happening to all living beings–so many species are disappearing at alarming rates. So there's a lot of layers here that I'm interested in.

One of the reasons I like installation art is because it has the potential to encourage a kind of active engagement. Walking through the gallery and interacting with each video, there’s an active kind of engagement there that is very different from sitting passively on the couch. I talk with my students about the importance of looking at the news and thinking about it actively and thinking about where information is coming from and decoding things. So, I’m interested in helping to foster that kind of viewership in my work (and in my teaching). And that kind of active engagement is furthered in the installation by inviting people to play catch. There's a bullpen in the gallery for people to play catch. So there are a lot of sad stories that I'm foregrounding in the installation, but there's also room for people to interact with it in a way that's maybe not as scary, by coming together through the poetics of the work.

So there's that, and that's to think through what's going on, but then there's also the website for the project: https://borderball.net - there is a webpage there inviting people to participate more. There's a webpage with information that I've gathered, with a collection of things that people can do. So I foregrounded a lot of stories, but there are a lot of people with so many more stories that people need to hear. And so there's a Tumblr page that we've created for people to share their stories about borders and immigration. And this is an issue that's happening all over the place. We are dealing with refugees all over the world. It is not specific to the United States. But sadly the United States is number one in terms of the amount of detention centers and people locked up in detention. So that's very sad. The resources page on borderball.net has a link to The Global Detention Project, which maps and analyzes detention practices and how governments are dealing with refugees all over the world. That's a site that's very much worth exploring, so people can figure out what to do. Freedom For Immigrants has a link on borderball.net too and they are dealing with what's happening here in the United States, and they have a really useful map of detention centers all over the country. The detention centers are not just at the border, they're all over the place and we don't know about this, you know? There's one right here in Forsyth County, North Carolina. There are immigrants getting locked up at the Forsyth County Jail. So it's not just at the border. There are lots of detention centers. And this has been going on for a long time. A lot of racist rhetoric was amplified during our previous presidency. But the detentions were happening before that presidency and are still happening. And so we are all complicit. And until all these detention centers are closed, in my mind, we have an ethical crisis. There is another organization called Close The Camps that's focusing on the detention centers here in the United States. Freedom For Immigrants has a number of ways for people to get directly involved in terms of volunteering their time and contributing in other ways. There are multiple ways for people to participate after seeing the movie and installation. Opportunities to learn more, to share stories, and to get directly involved with fixing the problems.

A - Wonderful list of resources, I will highlight them as well in this feature for everyone so that people can take action. We all must take action! We are all connected. We're all here in this ecosystem together, it is our collective home, our Mother Earth, and we have to take care of it, and we have to love and take care of each other. These are simple ideas and truths that we should have learned as children.

J - Right. Right.

A - We need to take these ideas about ethical responsibility into adulthood and really enact these ethical ways of being, which foster brotherhood and sisterhood and connections with other sentient beings on the planet and with nature, which is our environment, our home. So we need to take care of our home and each other. Your project really supports this idea and the idea of a kind of a planetary wellness, and offers a way into these challenging situations through art, through poetry and through direct action and shows us how we can all be a part of a solution. We can all be winners. Right? I just want to think for a moment about the specifics of your project Border-Ball and the form that it takes, because it's somewhat playful and that kind of playfulness and openness and poetry allow for a really beautiful way for people to engage conceptually with the project and with the ethical crisis you work addresses. You also provide great resources for people to use to get actively involved in being part of the solution. Border-Ball embodies concepts of winning and losing, struggle and opposition over territories, and resources, infrastructural resources and environmental resources. I mentioned environmental racism and injustice and the rigged nature of the system with elites vying for power and domination in a winner take all game. This context of a game that you've set up is a great way to contemplate this winner take all mentality and behavior we see by the US government, Russia and many others. It seems this is the political climate we exist in. A game as an aspect of art and politics, you embody it and complicate it so beautifully within this performance and this film. I think this work is remarkably sophisticated as a tool for foregrounding and amplifying the plight of millions of refugees and immigrants. Using the game as a way to think about battle or war. In game scenarios, there's always nationalism and regionalism and violence as part of the contest for domination. I mean, we could talk about the global conditions right now where a contest for world domination is being played out between superpowers and the citizens are pawns, used as shields, soldiers and “collateral damage”.

J - Yeah, such a great question and great points that you just raised. A few things I want to talk about in relation to what you said. I think, first of all, it's so true that so many of the big truths are things that we understand when we're kids. I did a project about sharing, and we seem to forget what that means, with all the poverty and inequality. And you also talked about how the news can be overwhelming because there's all this sadness. How do we engage with the horrors that are around us? Sometimes by looking at it in a different way. Playing catch is sort of an icebreaker, and sometimes adding some weirdness or a game can help us look at things differently and help remind us of ideas and beliefs that I think we all want and really still have.

I saw so much trauma when I was at the border, and it hit me. It's still actually hitting me. I also came away from there with a lot of hope because I talked with a lot of people—including really long conversations, over many periods of days, ongoing conversations with border patrol and detention center guards. There are people who are employed at the border and they, you know, are doing border patrol and are struggling with the ethics of this and wanting to do the right thing. Of course, some people are committed to doing the right thing more than others. People make mistakes. I think there's always hope for all of us to act better. I make mistakes. Everyone makes mistakes. That's something as a parent, you know, that I understand a bit more than I did before I had kids.

Playing catch is simple in a lot of ways. It’s something which many kids do, probably most people at some time or other in their lives have tossed a ball. And so it brings us back, I think, to an earlier time in our lives - and to very simple ideas and lessons we learned as kids. Playing catch is something that I've always really loved. I have fond memories of playing catch with people and talking about all kinds of things, while doing it. And it always felt right. It always made me smile, and I had to think about it, about why that was. And one of the reasons why, I think, is because there are simple rules, and the rules deal with equality. We are the same, no matter where we're from, it's the same rules. We have to respond to each other as equals. And we're also both giving and receiving. We are assuming control and relinquishing control. So we are responding to each other. So I'm giving up the ball, and then I am waiting for my turn, and then I'm taking it back or receiving it. I am responding to the other person's movements. I have to engage with them. I have to look at their bodies and their minds. I have to see them, and I have to respond to what they're doing. So there's a kind of physical interaction as equals. And the Wall and the Detention Center and all these other things in our society - our society heightens our differences. And when we highlight our differences, we fail to recognize our shared humanity. I think we get into a lot of trouble this way.

David Graeber, is a brilliant person who taught at Yale. I interviewed him for The Sharing Project a while ago. He just passed, but he's got this great new book, The Dawn Of Everything that talks about the Native American philosophical critique of European society. And the biggest one was, well: how can we allow people to be starving?

A - Oh God. Yes.

J - What's wrong with us? We are the richest country in the history of the world. We can be helping the people in our country, and elsewhere. I was just in Washington, D.C., and it's so striking to see the number of homeless people that are right at the Capitol. And so this is also about economics. There are these very wealthy neighborhoods all over the place, including in San Diego. And then we have people who are starving. We have people who are suffering, and we are closed off, and we are not just turning our backs on the suffering of others, but we are then treating them like prisoners and locking them up as prisoners in jumpsuits. And yes, we're helping some, but we are not helping nearly the number of people that we should. And so I'm walking every day and I'm seeing this giant wall, the Border Wall, and I'm seeing these multiple layers of walls at the Detention Center. And then I keep thinking about, well, what about our gated communities that are all over the country, where we're maintaining very strict boundaries, where we have these pockets of wealth? And then we have all these people who don't have anything. And it seems like our Border Wall and detention centers are an extension of that. It's a cultural thing. We've decided that we need walls around our big, wealthy, powerful country with this giant military and all these resources. And then we're being very guarded towards those people who need help and being very limited to what we offer. Is this what our four-year-old selves who were taught about sharing would do? There are kindergartens all over this country that teach sharing. So, how can we be acting in ways that directly contradict what we learned as kids?

And so this is an ethical thing. I was at the border for 40 days, very purposefully. I mentioned my religious Jewish upbringing. I don't practice organized religion now, but I have deep Jewish roots, with many generations of rabbis in my family’s tree. This is a very religious country, a Christian country in many ways, and the Bible is still the most widely read book of all time. I think there's a copy of it right over my shoulder. And, so 40 days, 40 days at Mount Sinai, 40 days, all these people immediately got it because we're such a religious culture. So like, okay, I'm walking every day for 40 days. We have to be talking about these things in relation to ethics. It's not about political parties. It's not about the Democrats, Republicans, Green Party, whatever. It's not. This is about ethics and responsibility. And it's about values that we, I think, all believe in and that we were taught as kids. And so if we think about those things and sort of break down our boundaries in ourselves and towards each other and interact as equals—like through the simple act of playing catch—then we might be able to think about things in a different way.

A - Beautiful. Really beautiful answer. Thank you so much for that. I'm really struck by the reality that there is abundance and plenty, and the idea of scarcity is a big lie perpetuated by a few people who are invested in the idea of keeping everything for themselves. I think often populations are just used as pawns in order to perpetuate this lie of scarcity and to create schisms and to divide and conquer people. When ultimately we're dealing with the human condition, which affects all of us, and no amount of wealth or privilege can change this fundamental reality. Creating an ivory tower scenario or a gated community can’t ultimately protect anybody from the reality of our shared condition as human beings. Nor can it protect anybody from the fact that there is greed and injustice which affects all of us in a negative way. We exist, and everything exists in an expanded field of consciousness, energy and ecology. We are all part of culture and connected in a relational way to each other and everything. Yet Corrupt power hungry governments , the Military Industrial Complex or Congress, along with greedy corporate entities are invested in sucking all of our resources from the earth.

This reality touches everybody. The refugee crisis is a global crisis, and it is very real, but it is based on the lie of scarcity and lack. As you’ve said, from a very young age, we are taught these tenets about sharing and being good to each other. You don't hit people, you don't steal from each other. Be good to people, be kind and generous. We're supposed to be good citizens and then suddenly that's totally perverted and turned into a scenario of control and domination by strategic actors who believe that somehow they have the right to control, dominate and exploit others for their own profit and gain. This is the sort of culture that we exist in. There's more money spent on the military budget than there is on education, housing and on public programs to help people. As you’ve said, there are plenty of resources, but they're misappropriated and allocated. I think art and activism ultimately must be part of the solution and must engage with a global intersectional culture and community. We can be propagandists, positive propagandists and agitators. Your work is an incredible gift to all of us because it offers a way into an awareness and activism that is incredibly generous and freeing. It allows people to engage in thinking about and talking about a mass trauma that is almost too painful to think about, but you're opening it up, opening a space, offering a way for people to engage, to get active and to be part of a solution for systemic change. Systemic change is really what we need, and we all must accept our collective ethical and moral responsibility to be part of the movement for a more humane world. We need systemic change, and I think your piece is really just beautiful in the way it encourages doing that. I thank you so much for your work, and I'm so happy that we have had this time to discuss it. I look forward to talking with you more in the future about your projects and to helping in whatever way I can. I want to actively be part of the change for positive growth and enlightenment in our culture. It's time for change in a massive systematic way.

Is there anything else you want to share with us?

J - I just really appreciate you, and I'm grateful. And it's such a joy to talk with you. And thank you so much for doing this. It's just so wonderful to connect with you again, and I appreciate all the work that you are doing. I'm just really glad to be part of what you're doing in this aspect of your work with Battery Journal. So thank you. Thank you so much.

A - Thank you