Algorithmic Painting in Physical Space: Vickie Vainionpää: Software & Siebren Versteeg: Up The Ghost

Algorithmic Painting in Physical Space: Vickie Vainionpää: Software & Siebren Versteeg: Up The Ghost

by Alex Feim

Installation view of Siebren Versteeg: Up The Ghost at bitforms. Image courtesy of bitforms and the artist.

What can an algorithmically generated painting look like in physical form? This is a question that two exhibitions downtown – Siebren Versteeg: Up The Ghost at bitforms and Vickie Vainionpää: Software at The Hole – attempt to unpack, but offer up diverging answers and possibilities.

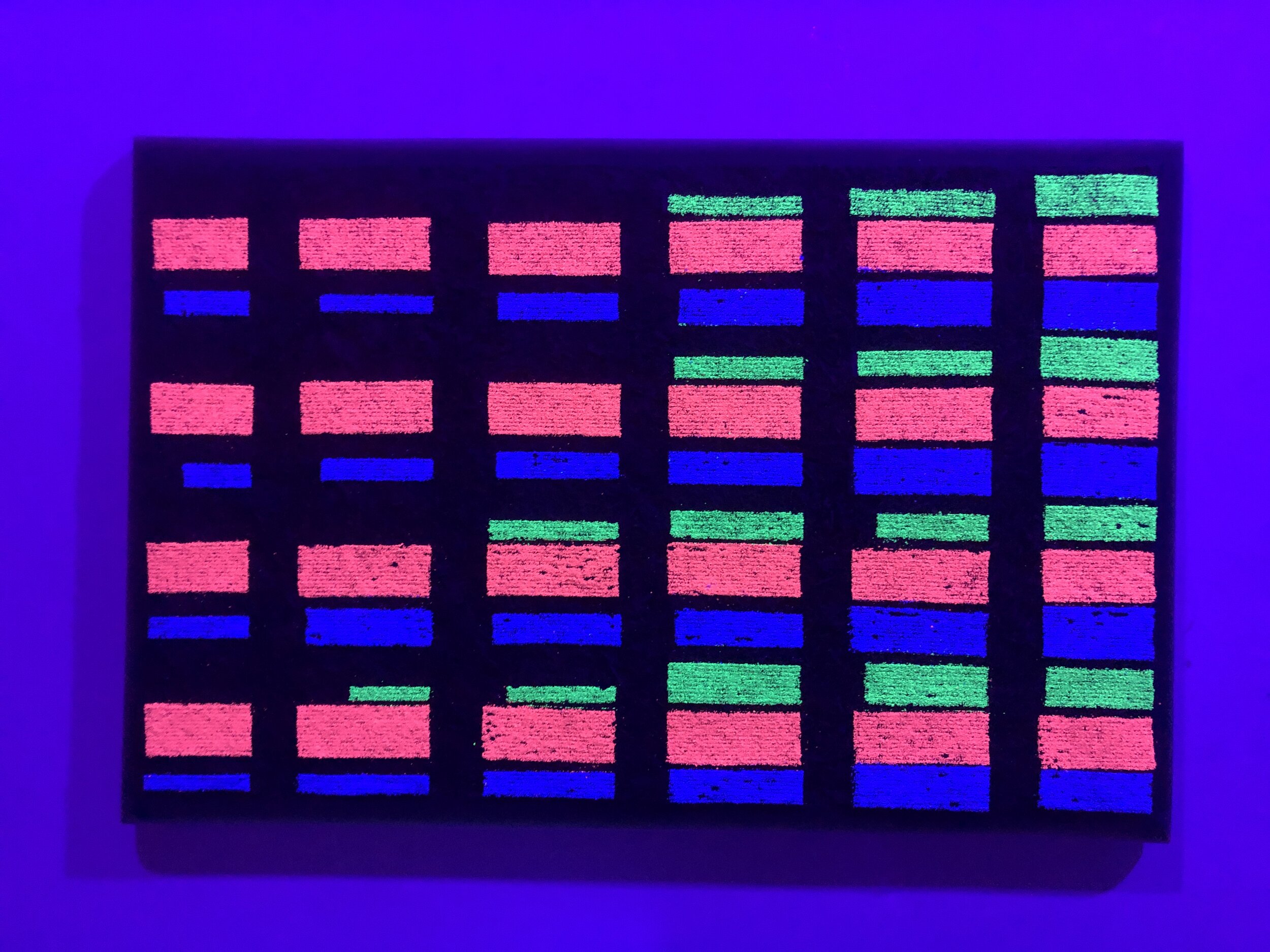

Installation view of Vickie Vainionpää: Software at The Hole. Image courtesy of The Hole and the artist.

Walking into The Hole’s Tribeca location, the viewer encounters a series of large-scale oil paintings of seductively colored biomorphic forms by Montreal-based artist Vickie Vainionpää in her debut New York solo exhibition Software. Continuing her “Soft Body Dynamics” series, Vainionpää builds her compositions by using an algorithm that generates a set number of forms per day, from which she then selects and paints in oil on canvas. The forms evoke body parts such as intestines, but also look decidedly digital and evoke an early 2010s Tumblr aesthetic, or perhaps an earlier Windows screensaver. From a distance, the paintings have a particularly glossy and smooth appearance, but paint is applied with a subtle stucco-like texture that gives them more depth when viewed in close proximity.

Vickie Vainionpää “Dark Mode,” 2022. 4k digital projection. Image courtesy of The Hole and the artist.

In the back room of the gallery, the same vocabulary of algorithmically generated biomorphic forms comes to life in “Dark Mode,” a 4K digital projection mapped across three walls, which is scored with a meditative synth soundtrack written by Montreal musician Nick Schofield. Here, the forms are rendered in darker colors and endlessly twist and morph into new versions of themselves. Though looped, there is a clear beginning and end to the cycle, which evades the work’s algorithmic ambitions. Next to the projection are two additional paintings – one on either side – which make use of the same darker color palette. At moments, the forms in the projection nearly exactly mimic the adjacent paintings, creating a brief uncanny sense of repetition.

Vickie Vainionpää, “Soft Body Dynamics 68,” 2022. Oil on canvas, 48 x 58 inches. Image courtesy of The Hole and the artist.

“The relationship between the body and technology is integral to Vainionpää’s symbiotic practice,” states the press release for Software. If that relationship is vital to the work, then what is elided is the actual nature of the relationship, and any sort of critical phenomenological engagement on the part of the viewer. As seductive and pleasurable as the forms are to look at, the work operates in the realm of techno-optimism, evoking the cyber-utopian rhetoric of Web3, and replicating traditional modes of gallery spectatorship.

While Vainionpää’s work offers an optimistic though perhaps ultimately innocuous take on the possibilities for algorithmically generated painting, Siebren Versteeg’s exhibition Up The Ghost at bitforms presents a multitude of oblique propositions for how algorithms and software might be used to create paintings and time-based generative work, and how these works might be presented and encountered by viewers in a gallery space.

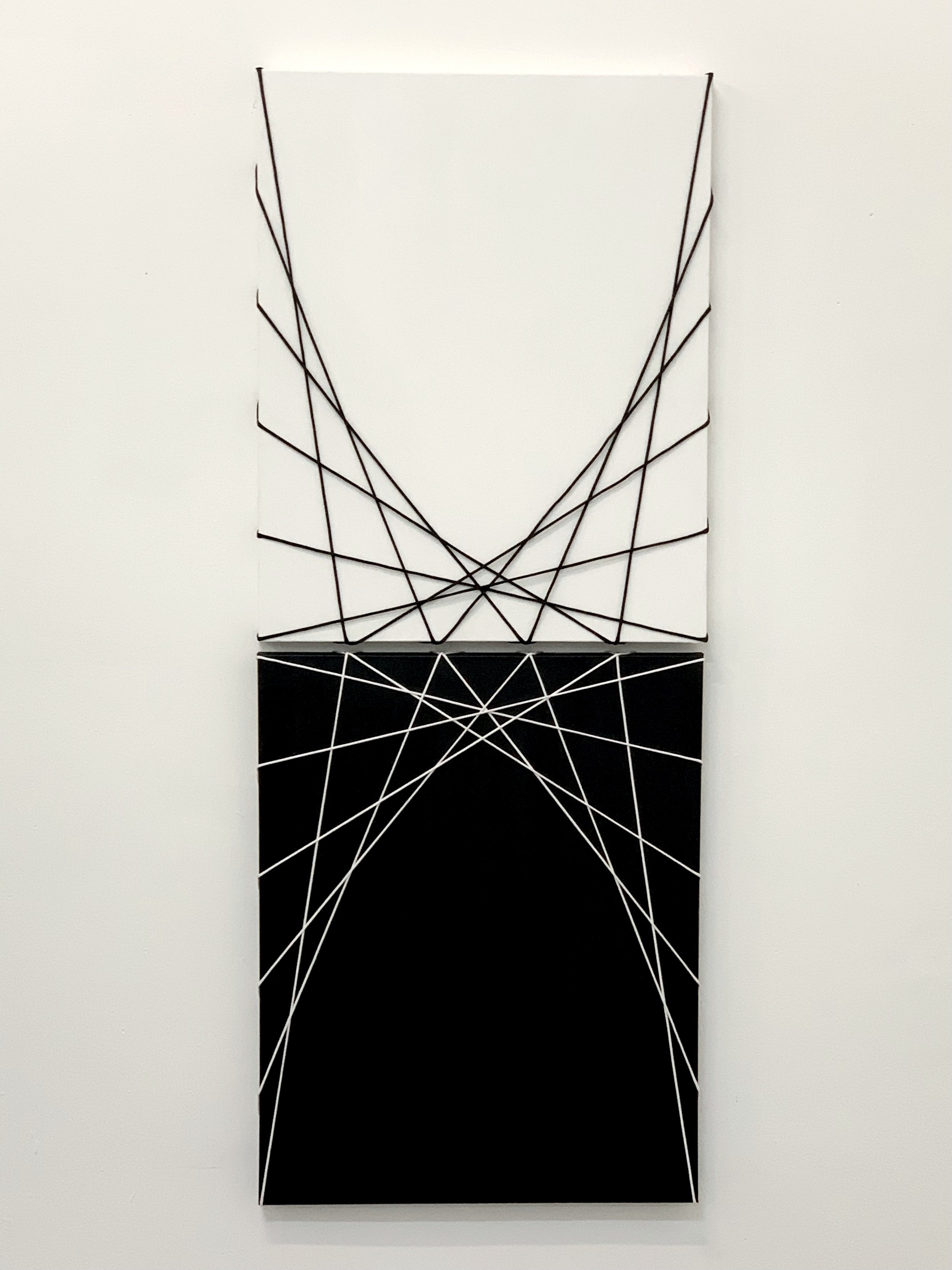

Installation view of Siebren Versteeg: Up The Ghost at bitforms. Image courtesy of bitforms and the artist.

As in Software, the viewer enters a traditionally lit gallery space – visible from the street via bitforms’ glass doors and windows – with two canvases on the walls in Up The Ghost. At first glance, these are paintings – but closer examination (and the checklist) reveals that both are algorithmically generated images that have been printed to canvas at an extremely high resolution. Looking closely, small imperfections true to printing rather than painting are visible, particularly in “Up the Ghost” (the exhibition’s namesake).

Installation view of Siebren Versteeg: Up The Ghost at bitforms. Image courtesy of bitforms and the artist.

Past the small entrance room, the viewer proceeds through a thick black curtain into the gallery’s main room. The experience of entering into this darkened room is at first a disorienting and overwhelming one – more than a dozen glowing images float on a “screen-like plane” that extends across the entire length of the space. The initial feeling is one of disembodiment and almost as if one is intruding into a sacred space. The feeling of disorientation gradually dissipates though, as one’s eyes adjust to the darkness, and the viewer moves throughout the space observing that some of the images are moving, mostly very slowly, while others remain static.

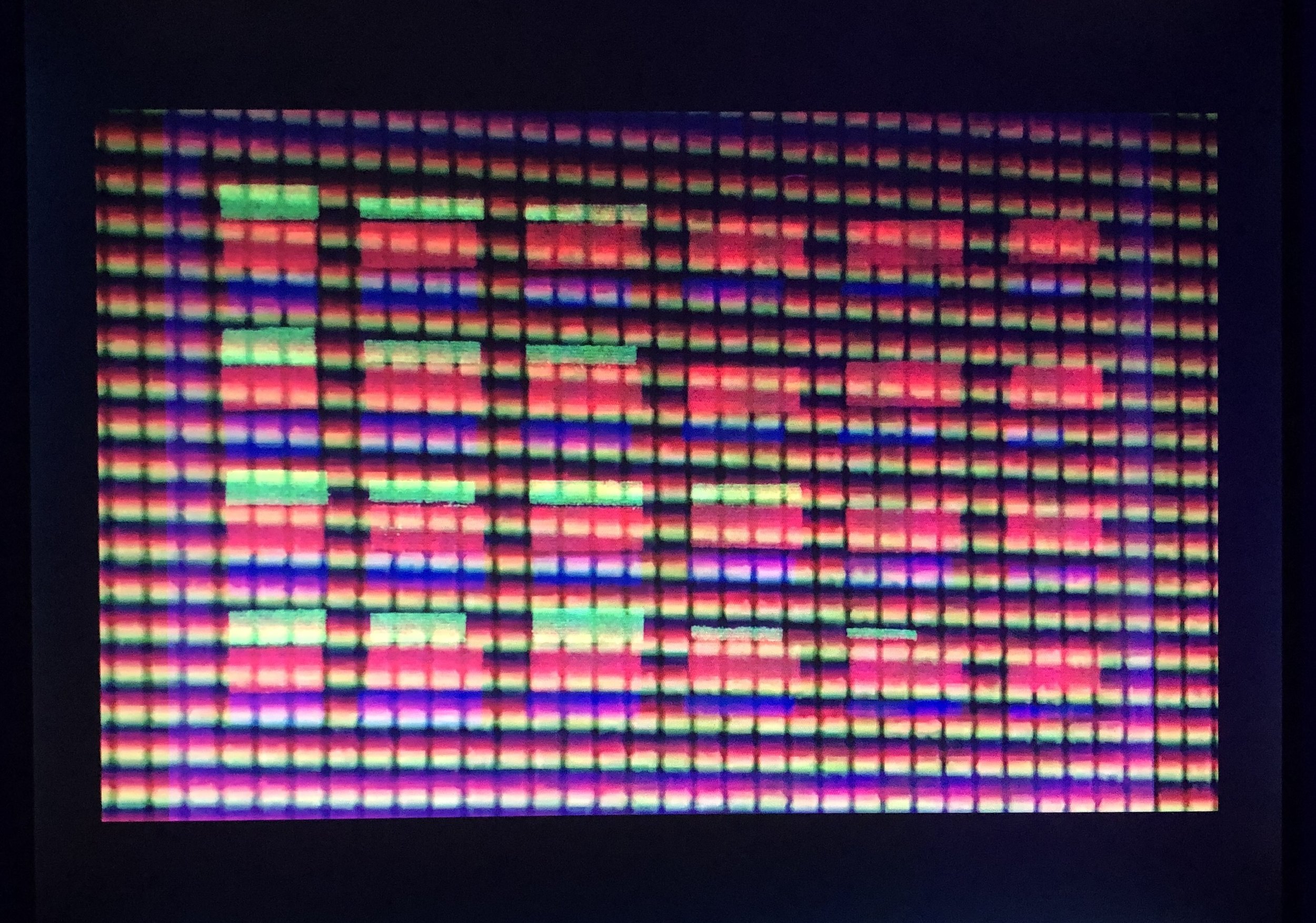

Siebren Versteeg, “Love Live x Five,” 2022. Custom software (color, silent), live webcam feed, subdomain, dimensions variable (Left) and Siebren Versteeg “The Location of the Image,” 2022. Custom software (color, sound), 22 x 12 in / 55.9 x 30.5 cm. Image courtesy of bitforms and the artist.

The image content ranges widely: an interactive touch screen “Hell Is Other People” allows the viewer to zoom in and out on a collaged collection of portraits and emojis; “Hopelessly Devoted” resembles a circular abstract painting, which slowly evolves, at once making and unmaking itself with newly generated brushstrokes; “Love Live x Five” livestreams a feed of a Robert Indiana LOVE sculpture at a conservation studio, which Versteeg and his sister inherited from their recently deceased father. The connecting tissue among these and the other works on view is that all of the image content is generated algorithmically or through custom software.

Siebren Versteeg “A Kind Of Past,” 2022. Algorithmically generated image, canvas

16 x 20 in / 40.6 x 50.8 cm, 400 DPI. Image courtesy of bitforms and the artist.

A glowing static image of a gestural abstract artwork toward the back of the gallery, “A Kind Of Past,” is particularly alluring, at least partially due to it being at eye level. Approaching it, the viewer may notice a projector overheard. This is not an image on a screen – despite its initial appearance as one – but a projection of a painting, as evidenced by the pixels visible when looking at it in close proximity. The pixels of the projected image echo the weave of a canvas in a clever sleight of hand between analog and digital. Shining an iPhone flashlight perpendicular to the surface onto which the image was projected in an attempt to figure out more about the technical support structures, the viewer may be surprised to learn that “A Kind Of Past” is in fact not a projected image of a painting, but rather a canvas with an algorithmically generated image printed on it, just like the two works in the first room. But here, the printed image is illuminated by the projector, casting pixelated light at a much lower resolution than the image was printed, which vastly intensifies the saturation of its colors so that it glows with the same vividness as the nearby images on screens. Pixelation and canvas weave intertwine and become nearly indistinguishable from each other, which confounds the boundaries between image, object, and screen.

Installation view of Siebren Versteeg: Up The Ghost at bitforms. Image courtesy of bitforms and the artist.

In less critically engaged work, such theatrics of being duped by a work’s mechanics and means of construction can come across as gimmicky or effect driven, and obfuscate the lack of actual substance. Yet nearly the inverse happens in Versteeg’s, where the work’s confounding of its own material existence by using visual trickery is its content, which opens outward nearly infinitely to questions of painting’s relationship to physical and digital realities.

If the criticism to be made of Vainionpää’s work is that it presents too glossy and polished of a take on algorithmically produced painting, then the challenge of Versteeg’s exhibition is almost entirely the opposite – that there may be too much going on for many viewers to fully comprehend. Yet, the work is not alienating in its form or content, and there is clarity to be gained from spending time with individual works and the exhibition as a whole. Images generated by algorithms or software in various possible forms and applications are the common thread, and the complexity of the ideas being executed in each work becomes evident as the viewer takes the time to read the individual texts for the works in the digital exhibition catalog, which is accessible via scannable QR code in the entry room of the gallery, or via the gallery’s website.

Installation view of Vickie Vainionpää: Software at The Hole. Image courtesy of The Hole and the artist.

The press release for Software states that Vainionpää’s work “embraces a type of cyborgism…exploring the symbiosis of humans and technology in a body of work that could only have been made through an interdependent collaboration between human and machine.” If cyborgism via the collaboration between human and machine is perhaps gestured toward in Vainionpää’s work, it is more fully enacted in Versteeg’s where the algorithmically generated paintings printed on canvas become something like bodies (or at least ghosts of them) which are then augmented via projected pixelated light to become higher forms of themselves. The viewers, too, embrace a kind of cyborgism when interacting with Versteeg’s work, though an everyday familiar form of it: the use of an iPhone. I shined my iPhone flashlight behind the screen-plane in an attempt to figure out more about the technical support structures, which revealed that more than one image was on the same monitor, whose physical presence was hidden in the darkness. It was through this supplementation of my own vision and embodiment as well that I was able to disentangle the complicated mechanics of the interaction between image, surface, screen, and projection in “A Kind Of Past” and the other canvas works in the main space.

The ways in which we encounter painting via digital images and become implicated as spectators continue to evolve rapidly. At its spring 2022 marquee auction, Christie’s no longer presented works themselves on auction blocks, but rather digital images of the works on LCD screens, making them appear, as Jason Farago observed, “as if a painting was one more nonfungible token (NFT), which it might as well be if it ends up…in a tax-exempt Swiss or Singaporean freeport.” With developments like this in how art is mediated and presented to audiences, it is important to continue to question the origins of images, whether glossy or ghostly, and the nature of our relationship with them.