Mary Frank: The Observing Heart

Mary Frank: The Observing Heart

Curated by David Hornung on view at Samuel Dorsky Museum of Art at SUNY New Paltz through July 17, 2022

Editors Choice by Anna Ehrsam

Mary Frank:The Observing Heart

To state that the artist and activist Mary Frank is a force of nature is an understatement. Her career spans over six decades, and at the age of 89 she is as powerful and prolific as ever. Her power, sensitivity and creative genius is evident in her current exhibition entitled Mary Frank:The Observing Heart, on view at Samuel Dorsky Museum of Art at SUNY New Paltz through July 17, 2022. This thoughtfully curated exhibition offers a unique opportunity to experience her sculpture, painting, drawings, prints, and photographs, produced during her illustrious six decade career. This exhibition embodies Frank’s deep connection to history, art, nature and life, fueled by her passion and dedication to the fight for social justice and the environment. “She is a connoisseur of the specific, the individual. Hers is a life of observation deeply informed by her wonderment at the natural world and empathy for the human condition. These are the two pillars of her world view, and she views them intertwined, in an eternal state of flux and transformation.” Mary believes that we are nature, and also political beings, existing in relation to our fellow creatures in a collective ecosphere and consciousness.

For Frank, her artistic formation started with growing up in the epicenter of New York City's East Village art world during the 50s and 60s with her mother who was also an artist. Frank speaks of her formative years, her love of her mother’s art books, and gravitating towards the non western canon and traditions; inspired by Pre Columbian, African, Indian and Chinese art forms, their materiality and direct expression. Frank also received support and mentoring from her community of artists and friends at an important formative time in her life. She went on to study dance with Martha Graham and painting and sculpture with Hans Hoffman and Max Beckmann. Frank’s community of artists such as Kerouac, Ginsburg, Steichen, Robert Frank, de Kooning, and Resnick, provided a rich environment for her creative growth as well. Her ideas and vocabulary are more aligned, however, with activist artist Henrietta Mantooth, the painter, sculptor and set designer Mimi Gross, and Peter Schumann, founder and director of the art activist collective Bread and Puppet Theater. She lives, and embodies her creative practice in a fluxus way. Her language is a unique cosmology of organic and expressive forms, with chance and randomness incorporated as part of her process. Her connection as a maker to her materials; wood, clay, plaster, pigment, stone, photography, drawing and dance, developed and took hold of her as she took hold of them, producing works with great strength, poetry and emotive power. She has said drawing is being, and her way of being and living in her creative process and flow resonates in the emotive power of her work. Frank produces iconic works of art which express love, sorrow, ecstasy, mourning and exultation. Mary Frank lives and works in New York City and Woodstock, New York.

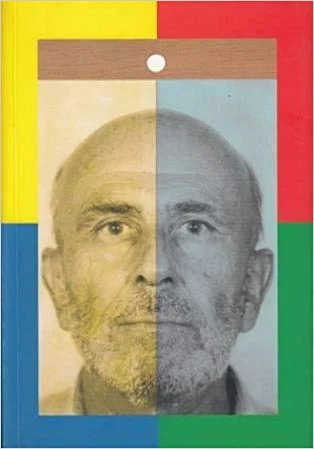

Mary Frank: The Observing Heart Catalogue

“Where is one working from? The observing heart. There is no way to make art. I can only make palpable experience.”

catalogue essay by David Hornung available

Mary Frank has always disliked generalities, easy answers, and ‘boxes’ built to contain and separate. A strong insistence on particularity is fundamental to her temperament. She is a connoisseur of the specific, the individual. Her’s is a life of observation deeply informed by her wonderment at the natural world and empathy for the human condition. These are the two pillars of her world view, and she views them intertwined, in an eternal state of flux and transformation.

As a familiar presence in the New York art scene of the nineteen fifties, Mary Frank was surrounded by some of the leading artists and writers of the time, among them Kerouac, Ginsburg, Steichen, de Kooning, and Resnick. She witnessed their heated debates about art on the stoops of galleries and at other impromptu gatherings. Manhattan was the epicenter of Abstract Expressionism and nascent Pop Art, and she was in the thick of it. But, despite the power of the personalities and the headiness of the conversation, Mary was drawn in a different direction. Theoretical speculation didn’t interest her; her artistic bias then and now, is for the direct expression of thought and feeling in pictorial form. The artists she admires most are those whose work is a direct reflection of their lived experience. More in line with her sensibilities than those New York luminaries of the fifties are narrative artists like the activist/artist Henrietta Mantooth, the painter, sculptor and set designer Mimi Gross, and Peter Schumann, founder and director of the Bread and Puppet Theater. Like Mary, all three work intuitively in a wide variety of materials to make art with dramatic impact. Jan Müller, a German émigré who made colorful and expressive paintings of figures situated in semi abstract settings was also a friend and early inspiration to her.

While in still in high school, between the years 1945 and 49, Mary Frank studied modern dance with Martha Graham. For a while she even entertained the idea of becoming a professional dancer. The stylized movement and grave, elemental postures of Graham’s choreography made an enduring impression on Mary’s burgeoning artistic sensibility. As a dancer, she learned about the figure in motion from the inside out. (Frank is largely self-taught and has said that studying with Martha Graham was “the only real education I had.”)

Mary Frank is, first and foremost, a storyteller preoccupied with the primal themes of human existence. But her narratives are not linear, and her work is not illustration. She seldom begins with a developed plan but builds spontaneously from part to whole. From the innovative clay figures that first brought her wide recognition to her most recent photographic works, Mary has favored this improvisational approach to making art. The finished work is arrived at somewhat circuitously, a sum of small choices, realignments, and adjustments. She is a connoisseur of surprise, an architect of the unexpected.

Unlike most artists who tend to specialize in one or two mediums, Mary has always been a brave explorer of tools, materials, and techniques. Over the course of almost seven decades, she has made sculptures, paintings, collages, prints, photographs, and myriad drawings. But it is not her mastery of tools and techniques that compels us: it is her vision of the world. Her primary focus has always been the urgency of expression.

Mary’s iconography is rigorously circumscribed and richly suggestive. Human figures, portentous birds, frightened horses, and mythic creatures that combine human and animal occupy stark vistas. Isolated caves, primitive temples, running walls and labyrinths evoke the rudiments of civilization and lend her images a sense of timelessness. Through her vigorous renderings of bodily posture, Mary’s protagonists present a wide range of emotion. Tender, fierce, mournful, fearful, or exuberant they run, leap, reach out or, when not in action, gaze in solemn contemplation. The faces, when shown, often wear a haunted expression. Mary’s world is typically a spare, rocky terrain of vast distances, windy shorelines and forbidding waters that brim with peril. Her darkest works are kin to Goya’s late “Black Paintings” and his powerful etchings, where human folly and suffering are unflinchingly presented and only the raw essentials shown.

At the heart of Mary’s artistic practice is drawing. While her major pieces employ memory and imagination, a life-long engagement with observational drawing helps her maintain an understanding of form and provides her images with a life-like specificity. Over the years she has filled the flat files of her studio with hundreds of drawings of people, places, animals, and plants. Her sketchbooks abound with studies made on site wherever she happens to be. For Mary Frank, drawing is more than a studio practice, it’s literally a way of being in the world.

Mary’s creative search also leads her to experiment with unconventional materials and processes. She paints on scrolls of drywall tape, doors, stones, and even mushrooms. She sometimes draws with scissors to make what she calls “shadow papers” which, when lit from behind, create an ethereal, dream-like effect.

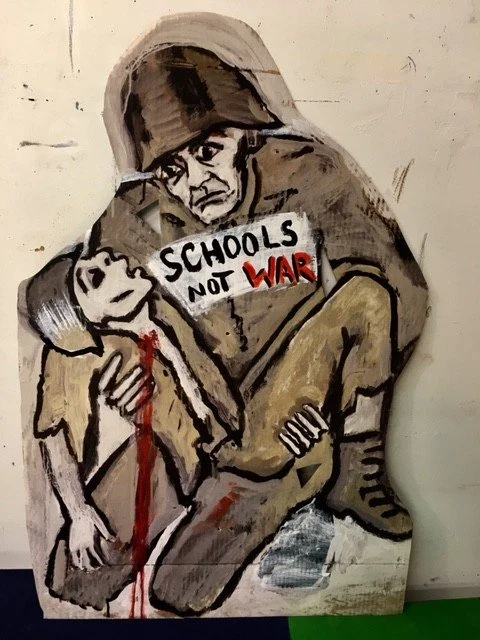

Over the years, Mary Frank has used her art to express concern, empathy, and outrage in response to major political and environmental events. A passionate advocate for social justice, she has produced placards and posters for countless protests. Through action and conversation, she actively promotes an awareness of both human suffering and our calamitous relationship with the natural world. In view of the latter, Mary has collaborated with Peter Matthiessen and Terry Tempest Williams on books with environmental themes.

Mary’s concern for the world and its people, often brings her out of the studio. Since the early 1990s, she has been a devoted advocate for Solar Cookers International, an organization that distributes solar cookers throughout the developing world. Its mission is to combat energy poverty in areas where fuel is not readily available by providing an alternative that leaves forests intact, reduces air pollution and frees women from the threat of rape while out gathering wood. Mary writes, “We cooked on the sidewalk outside the United Nations with 16 solar cookers: meat, rice, fish, bread, beans and purified water, for people from 44 countries. The fact is that everything can be cooked under the sun.” (For more information: https://www.solarcookers.org.)

This exhibition, part of the Dorky Museum’s “Hudson Valley Masters” series, draws from all periods of Mary Frank’s long artistic career and represents the full scope of her wide-ranging creative output. To this moment she remains a highly productive artist fully engaged with the world around her. This show captures her in mid-flight.

Written by David Hornung, Guest Curator, 2022 Dorsky Museum of Art

Mary Frank’s World On Display at The Dorsky Museum of Art

Review by Lynn Woods

Mary Frank: The Observing Heart, an elegant survey of the 89-year-old artist’s oeuvre of paintings, sculptures, prints, drawings, and posters at the Dorsky Museum of Art at SUNY New Paltz through July 17, spans decades, but the exhibition isn’t so much a retrospective as it is a walk through an imaginative world whose narratives about human suffering, love, loss, fear, and other aspects of the human condition resonate with the anxieties and fears of this moment. Frank’s pictorial language consists of archetypal nude or robed figures juxtaposed in some instances with looming faces and heads or mythological creatures. They move and gesticulate with the grace of dancers, and along with plant, bird and animal forms and architectural fragments, they inhabit stark, elemental landscapes with rocky precipices and turbulent seas. The imagery suggests ancient iconographies, which speak to the universal — an effect heightened by the rough texture of the paint and palette of earthy reds, black, and gray, as if the works were painted not on board or wood panel but on the walls of a cave. Frank’s intuitive approach to making art, which extends to painting on a fungus, “drawing with light” by cutting incisions into a piece of paper with scissors that is then suspended in a window, and positioning a cut-out silhouette of a head or a figure over a piece of charred wood or green leaf to create an image of startling originality — an inventiveness reminiscent of Picasso — has been enriched over the years as she recycles her paintings and small sculptures into new works of art and expands on her themes. The result is an amazing coherence and consistency, a totality of vision that is indifferent to issues of style. “The pleasure of a good exhibition is to really connect with viewers and give them an experience maybe they never had before, that has real meaning, rather than me making a statement,” Frank said recently in a phone conversation. “Hopefully it’s one that leads them to action” — an imperative for Frank herself, whose activism on numerous causes has centered in the past two decades on Solar Cookers International, an organization that distributes solar cookers throughout the developing world.

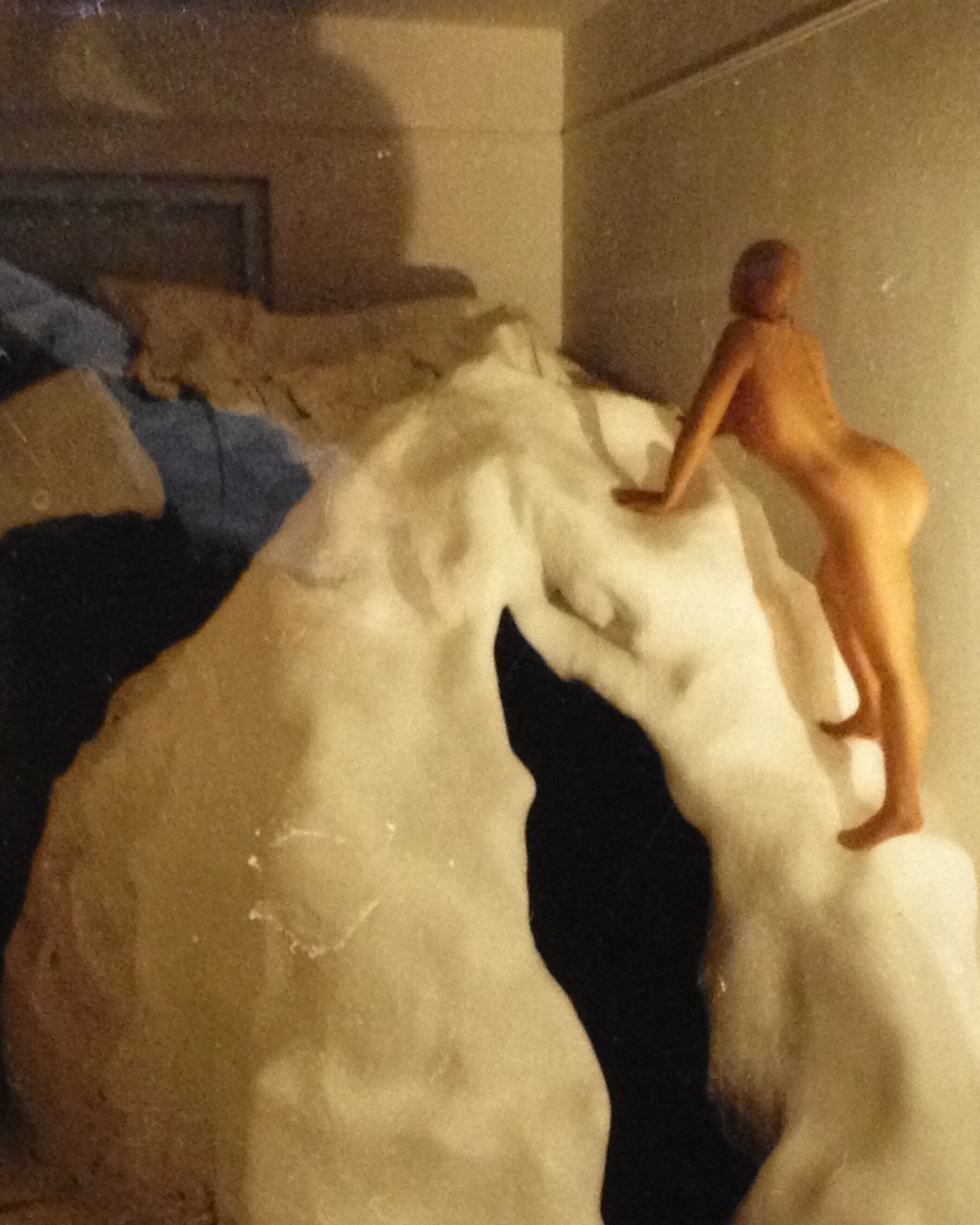

Lift by Mary Frank, 2021.

The earliest work is a wood carving of a figure, entitled Winged Woman, that dates from 1958, when Frank was a young mother living in Greenwich Village just getting her start as an artist. (She was born in London, moved to New York City with her mother at age seven to escape the Blitz, studied with Martha Graham as a high school student, and married photographer Robert Frank at age 17, a union later leading to divorce and Frank’s struggle to support her two children while devoting herself to art.) Her first show was of these carved wood sculptures in the early 1960s; tellingly, her influence was not the Abstract Expressionists with whom she rubbed shoulders but the ancient Egyptian sculptures she saw at the Met.

The large paintings on the gallery walls, which can roughly be categorized as Blake-like howling wildernesses engulfing human figures and animals and more somber, totemic-like compositions in which a series of miniature narrative tableaux are arranged like pictographs in a rough grid, are complemented by numerous sculptures, most of them of fired clay and depicting reclining or dancing figures, nudes on horseback and large heads. The sculptures date from the late 1960s, 1970s and 1980s (and are considered by many to represent the pinnacle of Frank’s career), which were followed by the paintings starting in the 1990s. A surprising number of the paintings, however, were made in the past four years — strong works showing an artist still in her prime (or, as curator David Hornung writes in the catalog essay, “mid flight”). Their suggestive narratives, in which small, naked figures float, swim, leap, run, crouch or raise their hands in despair or ecstasy in the depths of tsunami-like waves or cosmic whirlwinds, which threaten to whisk away all of human history, speak powerfully to the predicament of a world on the brink of ecocide; the fiery reds and savage blacks seem to address, presciently, the horror of war that is now wreaking death and destruction in Ukraine and possibly could engulf the planet. Arcadia has deserted the bathers of Picasso and Matisse, who now find themselves marooned in chaos. Human or animal spirit guides, conveyance by boats or horses, and jumps in scale between the forms, which simultaneously suggest confinement and vast space, intimacy and isolation, suggest states of consciousness and transformation, but in much of the recent work, in particular, there can be no doubt that the stakes are survival.

Among the most powerful of these works is Translation of Bird Calls, from 2018-19, in which nature is literally represented by a large collaged leaf, a fan-like shape whose surface is covered in intricate tracery, which is being consumed by flames rising from a rocky precipice in the lower left-hand corner; the reddish atmosphere, riven with white smoke, the receding fragments of labyrinths, suggesting broken civilizations, and the swooping, dark form of a woman trying to escape, convey a powerful sense of cataclysm. What might in the past have been thought mainly as metaphors of the human condition now have a frightening urgency, even as Frank offers images of hope — for example, the white bird whose broad uplifted wings extend off the canvas, suggesting solace and protection, even as its half-opened peak could also signal alarm; such ambiguities and double meanings are characteristic of Frank’s work.

The clay sculptures explore these ideas through more purely formal means. The three-dimensional forms of her figures, horses and heads are conceived as hollow volumes fragmented by and extending out into space. In Horse and Rider, a reclining nude figure, her legs cut off at the knees, raises a hand to her buttock, as if to spur herself, not the two halves of the horse, which her body bridges, forward. The truncated horse is in full gallop, surmounting undulating, fabric-like folds of clay that describe its forward momentum; mass is subsumed to energy, as the clay is used to dematerialize the solid animal into moving force. Frank similarly uses clay to describe the movement of the bodies and swirling robes in the Three Dancers, a grouping that recalls Rodin’s Burghers of Calais. Her conception is lyrical, rather than the geometrical, analytic approach of the Cubists, and the effect is one of ineffable grace. Nighthead, a large head sliced through the middle to reveal a painting of a blue figure crossing two planes opened up like the pages of a book, ingenuously suggests the head as the generator of dreams, of a consciousness that flows beyond its physical confines.

Horizon Bird by Mary Frank, 2012.

Sculpting clay enabled Frank to interpret the fluidness of her active forms by conceiving them as fragments of a whole, resulting in a flexibility of execution and meaning. Her reclining figures, for example, suggest both death-like repose and resurgent energy. Consisting of ceramic pieces fired separately then pieced together on the bare ground, these signature works of pathos and playfulness, in which the viewer’s imagination fills in the spaces between the forms, evolved from the limitation of using a kiln that was too small to fire an entire figure, noted the artist. “I made a head in clay and then decided to continue the body, which had to be in pieces. I liked making ten legs, which you can move around and were all different. An arm could be like a wing or a band. It gave me tremendous freedom.” (One of these recumbent figure pieces in the show, Lover, is actually bronze, cast from the original clay sculpture.)

Such improvising, which encompasses the use of collage in her two-dimensional pieces to incorporate a variety of mediums and materials, such as stones, leaves, twigs and other natural materials, is key to her process, which is one of discovery. This quest infuses her work with a freshness of vision whose contradictory impulses and pivotal meanings in turn engage and challenge the viewer.

The sensitive curatorial touch of Hornung, an accomplished artist himself, has resulted in a flowing rhythm of paintings and sculptures in the main gallery space, with ample room, lending a sense of expansiveness to the viewing experience. That contrasts with the density of works hung salon-style in the back room, which conveys the intimacy and processes of the artist’s studio. Drawings are the raw content from which the works evolve, and so it is fascinating to observe the many sheets of figures, animals and birds in ink, charcoal, and pastel clustered on the wall. There is also a wall of monotypes, each like a Frank painting in miniature except with shapes more clear-edged, a beautiful modulation of tones, a luminosity of color, and a more graphic contrast of black and white, suggesting the delicacy of Japanese sumi art.

Our Only Home by Mary Frank, 2016.

There is also a display of archival pigment prints, the name given to the tableaux of paintings, drawings, small sculptures, natural objects and cut-out paper assembled collage-like on the studio’s concrete floor and photographed by Frank, which is then printed and framed as the artwork. The prints, which sometimes incorporate water and a fish bowl in their imagery, have been collected in a book entitled Pilgrimage, with text by art critic John Yau and a poem by Terry Tempest Williams. There is also a large papier mache sculpture, entitled Chimera, of a snarling lion with a red deer head emerging from its back. And finally, there is a display of the posters Frank has designed for a plethora of causes, related to war, social justice, environmental destruction and women’s issues (some viewers may recognize her “Don’t Tear Families Apart” poster addressing former president Trump’s cruel family separation policy at the border).

Frank has exhibited at major museums (her large triptych What Color Lament? is on loan from the Whitney Museum of American Art) and received numerous awards, including two Guggenheim fellowships. She has illustrated books by Peter Matthiessen and others and been the subject of many books herself. For many years she has been represented by the Elena Zang Gallery, located here in Woodstock, where she resides half the year, and D.C. Moore, in New York City, where she and her husband, Leo Treitler, a musicologist, writer and pianist, live the other half. An excellent documentary film by John Cohen, entitled Visions of Mary Frank, can be viewed on a screen in the gallery. “The Observing Heart” is on display at the Dorsky through July 17. The museum is open Wed. through Sun., from 11 a.m. to 5 p.m. (closed for spring break March 12-20).

VR Walk Through of the Observing Heart

BIO

Born in London, England, in 1933 Mary Frank moved to the United States with her family in 1940. In the early 1950s she studied with Hans Hoffman and Max Beckmann. Frank works across disciplines as a sculptor, painter, photographer and gifted ceramic artist. Without allegiance to any particular way of working or medium, Frank is fueled by her ever present urge for direct and honest expression. Frank's process begins with some form of abstraction from which she teases out what she describes as a pre-existing time and atmosphere where events can take place. Her recurring imagery act as an alphabet, combined in order to evoke feelings of grief, love, sorrow, ecstasy, mourning and exultation.

Mary Frank has been the subject of numerous museum exhibitions, including a retrospective organized by the Neuberger Museum in Purchase, New York in 1978; an in-depth look at her Persephone Series at the Brooklyn Museum in 1988; and Natural Histories, organized by the DeCordova Museum in 1988 which traveled to the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts and the Everson Museum of Art. In 2000, the Neuberger presented Encounters, a major traveling retrospective accompanied by a book by Linda Nochlin. In 2003, Experiences, a solo exhibition of Mary Frank’s paintings was organized by the Marsh Art Gallery, University of Richmond. In 1990 a major survey of Mary Frank's work, written by Hayden Herrera, was published by Abrams, New York. Shadows of Africa, a collaboration between the artist and poet Peter Matthiessen, was published by Abrams in 1992.

Frank's work is in the collection of numerous institutions including the Art Institute of Chicago, IL, the Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, Washington, DC , the Jewish Museum, New York, the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, the Museum of Modern Art, New York, the National Museum of American Art, Washington, DC, the Newark Museum, NJ, the Whitney Museum of American Art, New York and Yale University Art Gallery, New Haven, CT. Frank lives and works in New York City and Woodstock, New York.

Acknowledgements:

Images and text courtesy of Mary Frank, DC Moore Gallery and the Samuel Dorsky Museum of Art.

Special photo credit to Bob Wagner.

Artist | Writer | Visionary