PORTABLE DEVICE #1: Revisionary Repair Service

PORTABLE DEVICE

reports from various locations by Sarah Falkner

Michael Tong

Revisionary Repair Service

Gallery @ 46 Green Street, Hudson NY

service extended until 29 September 2018 - completed works on view through 7 October 2018

michaeltongstudio.com 46greenstreetstudios.com

PORTABLE DEVICE is a series of BATTERY dispatches about art and cultural practitioners, producers, and entities I encounter in the course of my semi-nomadism. PD #1 reports from Hudson, New York--a place I have been spending a lot of time in regularly since 2001.

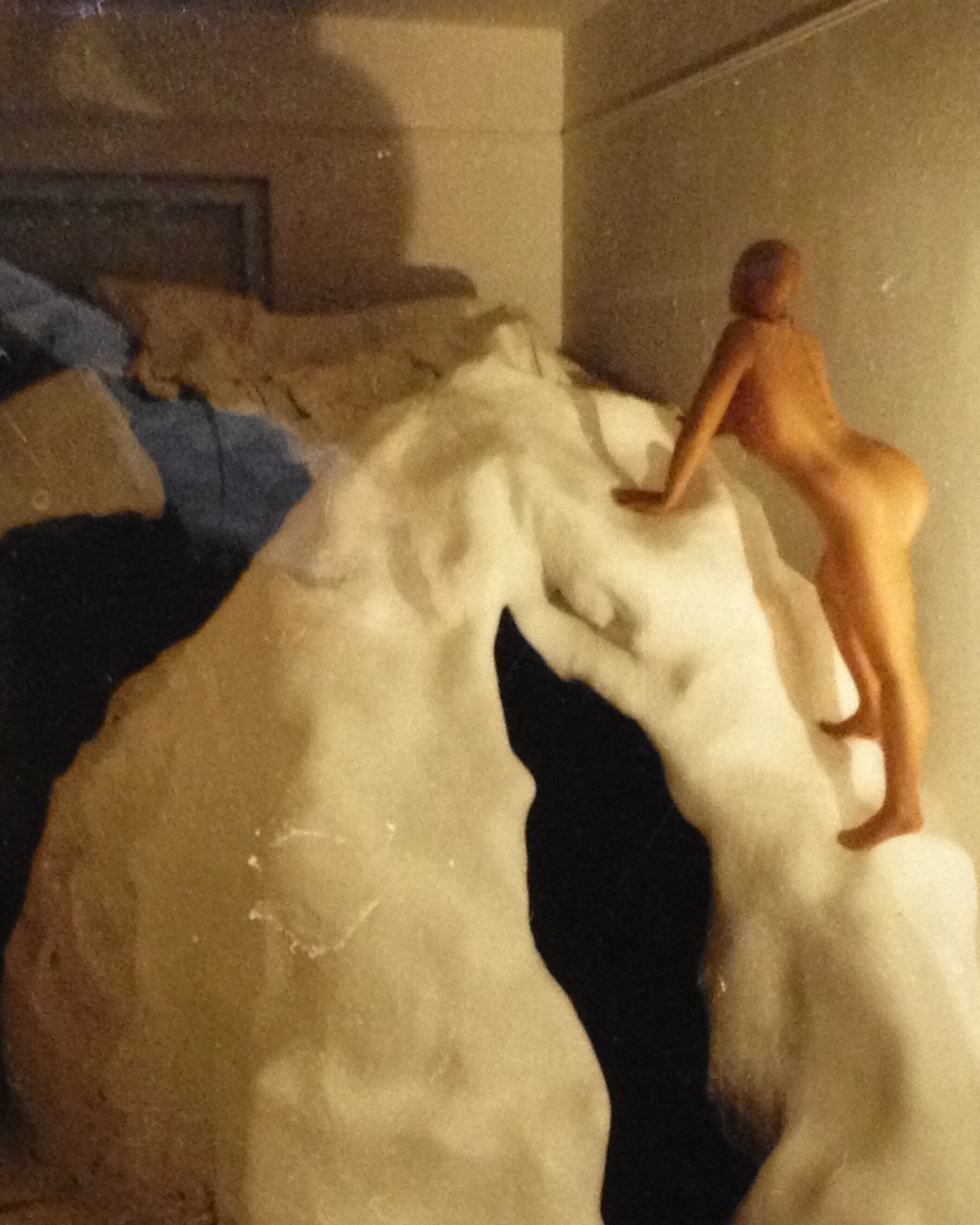

“Revisionary Repair Service” is a multi-disciplinary mixed media site specific performance installation that interacts and connects with the community of Hudson and beyond. For the duration of the exhibition, artist Michael Tong will be on site at the Gallery to perform repair work on specific broken items brought forth by the community at large. After the items are examined for their feasibility, the chosen ones will be repaired as well as repurposed.

—Michael Tong

Michael Tong's artistic practice includes both studio practice in sculptural and drawing media, as well as public interactive pieces intersecting social intervention, social practice, and durational performance. Tong has lived for five weeks in a steel Buddha head of his own construction at Exit Art, created social spaces for teatime conversation and divination through the I Ching, and forged new non-religious fire-based rituals where participants joined together to cook food in sculptural functional barbecues or collectively cleanse of mental baggage through the burning of story-heavy objects of their choosing. Tong also teaches at Parsons School of Design.

Revisionary Repair Service manages to bring all of Tong's individual and social practices together in one ingenious cross-pollination, and my first experience beholding the objects on view during a mid-way “progress report” evening event was emotionally and psychologically complex and absorbing. As I made my way through the crowd, before I could take a look at the artist statement I encountered an acquaintance of mine, a charming and free-spirited elder whom I know to have lived and moved across the country multiple times in the course of her life, apparently quite unafraid to uproot or let go of physical and emotional freight. Yet when I saw her at the gallery she excitedly pulled me over to see the object that Tong had revised for her: a porcelain statue of a cartoonish big-eyed Bambi-spotted fawn whose legs had neatly broken many years previously, which she had always loved as a child and which “for some strange reason” had carried with her—both fawn, and broken-off legs--all these years, even through her peripatetic years in which she has jettisoned several houses, husbands, and many personal effects. The revised fawn now rests comfortably supported upright by a red-painted plaster sculpture that calls to my mind Salvador Dali's Mae West Sofa and which cradles the fragile little forelegs in a privileged spot where the fawn appears to gaze upon them with as much affection and devotion as my friend has for her childhood treasure. The effect of the transformed object reminded me of old Catholic saint devotional images and reliquaries, where the central figure has transcended the violence of a bodily harm inflicted upon it and proffers a triumphant gestalt of itself and its affliction as an object of veneration. Another piece on view that evening that held my attention through the crowd was the frame of a bamboo and rattan couch that had its limbs and joints rejoined and strengthened with plaster gauze applied in a fashion reminiscent of old fashioned plaster casts such as what my grade-school classmates would sport following a mishap with a skateboard—it felt as if the couch were healing from recent injuries, and re-animated the material in such a way that made me feel I had previously been rude to treat it like a piece of furniture rather than a living thing.

I returned to Tom McGill's Green Street gallery a few days later to speak with Tong to discuss the project and his process. During the piece he is onsite in an active workshop adjacent to the gallery space where finished pieces are displayed. He begins with a careful assessment of each object a person brings him, first determining whether it can be returned to performing its original function using mostly low-tech materials he keeps on hand for his sculptural studio practice—plaster, wood, clay. If the object cannot be repaired, it is revised: resurrected and transformed, but very much not “restored” as we have come to think of the term.

Wherever they land on the spectrum from repaired to revised, the completed objects flaunt their brokenness and imperfection. I asked Tong whether there was any relationship for him with Kintsugi or other wabi-sabi practices in which breakage is repaired while accentuating the imperfection in a highly aestheticized fashion, and he replied that his work was about something very different--to use the language of Marxist dialogue, it is much more of an anti-commodity fetishism.

When I visited the second time, Tong was in the act of revising what he described as a “fake fireplace,” a mass-produced metal and glass simulation of burning logs and embers in a grate, which he told me he was “stripping down to its essence” by removing extraneous pieces of metal, removing elements that “seem unpurposeful.” He told me that when it is clear a piece is a revision, the process involves a sort of “cleansing” before rebuilding, in which the object is somewhat destroyed to a point of clarity where he can see what the “really nice thing” about the object really is. Some objects remain spare and unadorned and are united with another austere element into a new life joined together towards a common purpose, such as Dirty Ellsworth, in which a rusty saw blade and a simply-machined strip of wood unite to evoke the elegant forms of Ellsworth Kelly's compositions. Other times, Tong schools even the most humble media in super-sophisticated language, such as a baroque gilded and painted porcelain vase where Tong has devised a gloopy plaster prosthesis, a heavy and theoretically-incongruent addition whose sinewy curves somehow still manage to embolden it to be an effective equal partner to the original still-intact handle. The vase has been returned to performing its original function.

Tong told me that in Revisionary Repair, compared to his previous social practice pieces he talks less with people—who tend to drop off their objects—and spends much more time with the objects themselves, which have been a surprisingly varied spectrum of unique challenges. He says he is always “a little shocked” when he first encounters an object, experiencing a moment of anxiety and feeling “what am I supposed to do with this?” before he proceeds to determining whether the object will be repaired or revised--and then, how. He has on hand two reference books, Zen and the Art of Motorcyle Maintenance and Shop Class as Soulcraft, both of which he finds helpful with problem-solving, because “Once you realize there is an emotional framework to the process, you're better off.”

Though Revisionary Repair has a self-imposed materials constraint to work within the range of Tong's existing sculptural media, sometimes he will research how to repair a thing. A major inspiration for Revisionary Repair was his purchasing a home outside of Hudson and entering a new territory of repairs and maintenance, which even a person with a strong sculpture and design background and DIY ethos can find difficult to navigate at times. He notes that RR is also informed by his experience being father to a young child, which also follows a similar, familiar pattern: being a little bit scared, doing a lot of research, experimenting, worrying, trusting your instincts, following some guidelines, and figuring it out. Another of my favorite objects on view is Father and Son, in which two stovetop espresso pots are joined so that the smaller seems sheltered and mentored by the larger, whom it resembles exactly.

Sitting with Revisionary Repair's array of disparate objects--often somewhat forlorn mass-produced objects that have been cobbled and cajoled into individual presences with lively personalities and affects—is a quietly powerful meditation on our contemporary moment in late stage consumer capitalism. As the Doctrine of Planned Obsolescence cuts ever shorter the lives of all our manufactured gadgets and devices, and industrial design is often pressganged into exclusive service for Shareholder Profit, Ordinary Humans find it ever less possible to make, repair, or prolong the lives of objects now vital to our jobs and roles as responsible citizens in a crumbling empire. In the complexity of normalizing that we purchase, for example, a new sweatshop-assembled, slave-mined mineral-dependent smartphone every 2.5 years, any person with a conscience must spend their days in and out of cognitive dissonance, increasingly alienated from other people and our environment. Our relationships with objects and each other are in dire need of intervention and transformation; Revisionary Repair inventively unravels the false binary of consumption and disposal, and also finds room for some sophisticated aesthetics, contemplation, and community to enter the equation.

CLICK ON THE IMAGE BELOW FOR A SLIDE SHOW